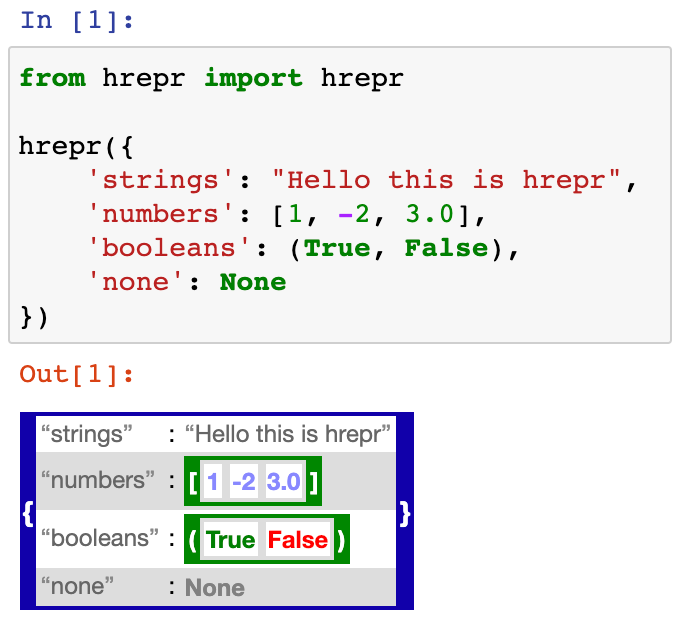

hrepr outputs HTML/pretty representations for Python objects.

✅ Nice, colourful representations of lists, dicts, dataclasses, booleans...

✅ Ridiculously extensible and configurable

✅ Handles recursive data structures

✅ Compatible with Jupyter notebooks

I suggest studying the example file to learn hrepr:

python examples/exhibit.py > exhibit.html(and then view the HTML file)

Also see the Jupyter notebook at examples/Basics.ipynb, but keep in mind that GitHub can't display it properly because of the injected styles/scripts.

pip install hreprfrom hrepr import hrepr

obj = {'potatoes': [1, 2, 3], 'bananas': {'cantaloups': 8}}

# Print the HTML representation of obj

print(hrepr(obj))

# Wrap the representation in <html><body> tags and embed the default

# css style files in a standalone page, which is saved to obj.html

hrepr.page(obj, file="obj.html")In a Jupyter Notebook, you can return hrepr(obj) from any cell and it will show its representation for you. You can also write display_html(hrepr(obj)).

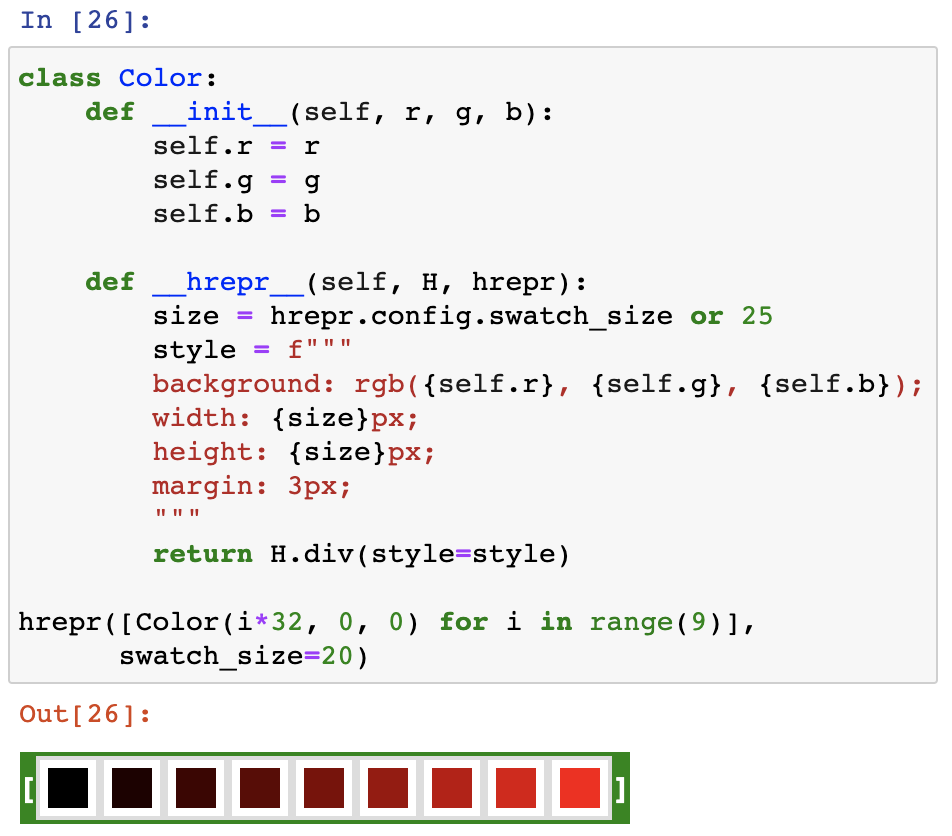

A custom representation for an object can be defined using the following three methods (it is not necessary to define all of them, only those that are relevant to your case):

__hrepr__(self, H, hrepr)returns the normal HTML representation.- Use

H.span["some-class"](some-content, some_attr=some_value)to generate HTML. - Use

hrepr(self.x)to generate the representation for some subfieldx. hrepr.configcontains any keyword arguments given in the top level call tohrepr. For instance, if you callhrepr(obj, blah=3), thenhrepr.config.blah == 3in all calls to__hrepr__down the line (the default value for all keys isNone).

- Use

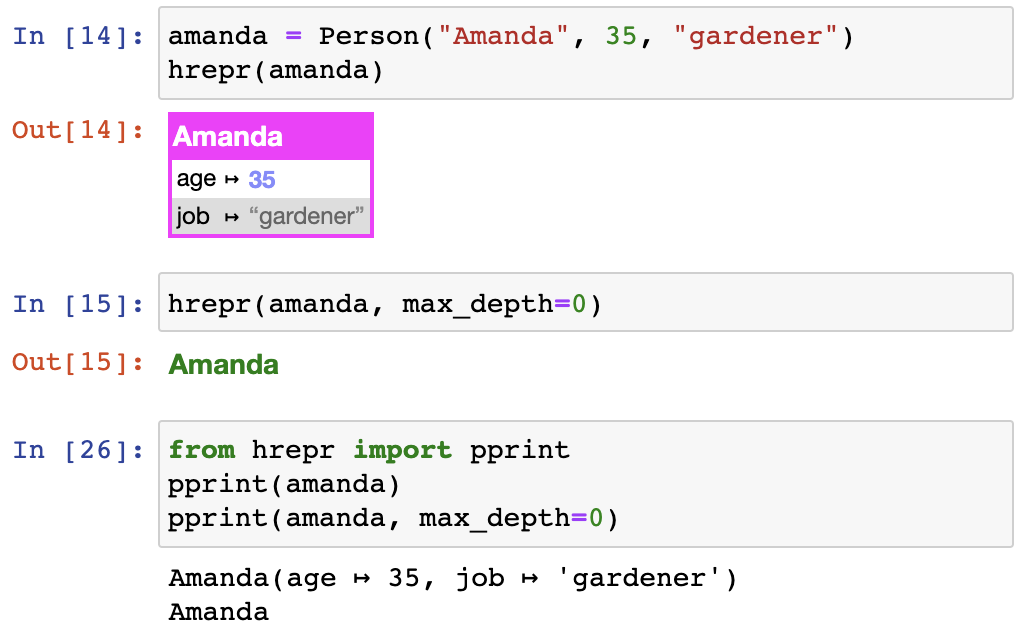

__hrepr_short__(self, H, hrepr)returns a short representation, ideally of a constant size.- The output of this method is used when we hit max depth, or for repeated references.

- Only include bare minimum information. Short means short.

__hrepr_resources__(cls, H)is a classmethod that returns resources common to all instances of the class (typically a stylesheet or a script).- When generating a page, the resources will go in

<head>. - You can return a list of resources.

- When generating a page, the resources will go in

No dependency on hrepr is necessary.

For example:

class Person:

def __init__(self, name, age, job):

self.name = name

self.age = age

self.job = job

@classmethod

def __hrepr_resources__(cls, H):

# Note: you might need to add "!important" next to some rules if

# they conflict with defaults from hrepr's own CSS.

return H.style("""

.person {

background: magenta !important;

border-color: magenta !important;

}

.person-short { font-weight: bold; color: green; }

""")

def __hrepr__(self, H, hrepr):

# hrepr.make.instance is a helper to show a table with a header that

# describes some kind of object

return hrepr.make.instance(

title=self.name,

fields=[["age", self.age], ["job", self.job]],

delimiter=" ↦ ",

type="person",

)

def __hrepr_short__(self, H, hrepr):

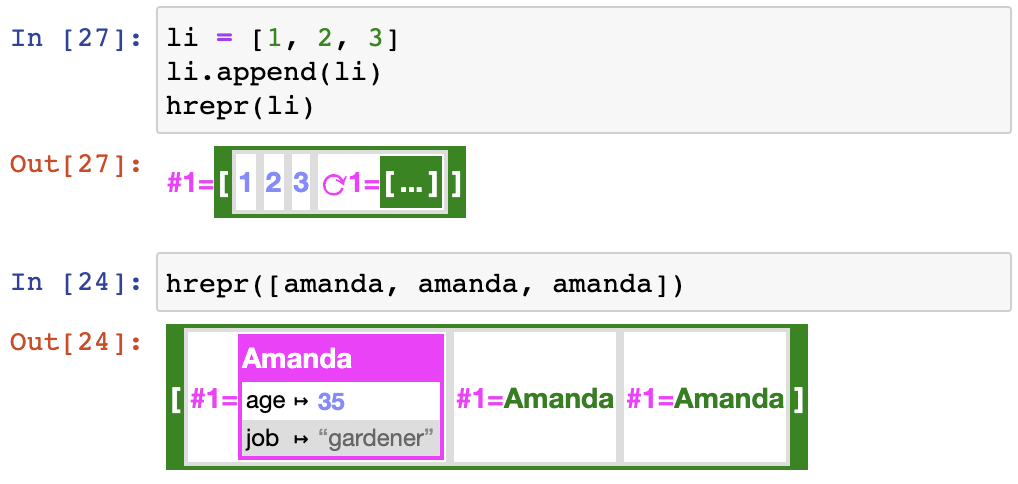

return H.span["person-short"](self.name)hrepr can handle circular references. Furthermore, if an object is found at several places in a structure, only the first occurrence will be printed in full, and any other will be a numeric reference mapped to the short representation for the object. It looks like this:

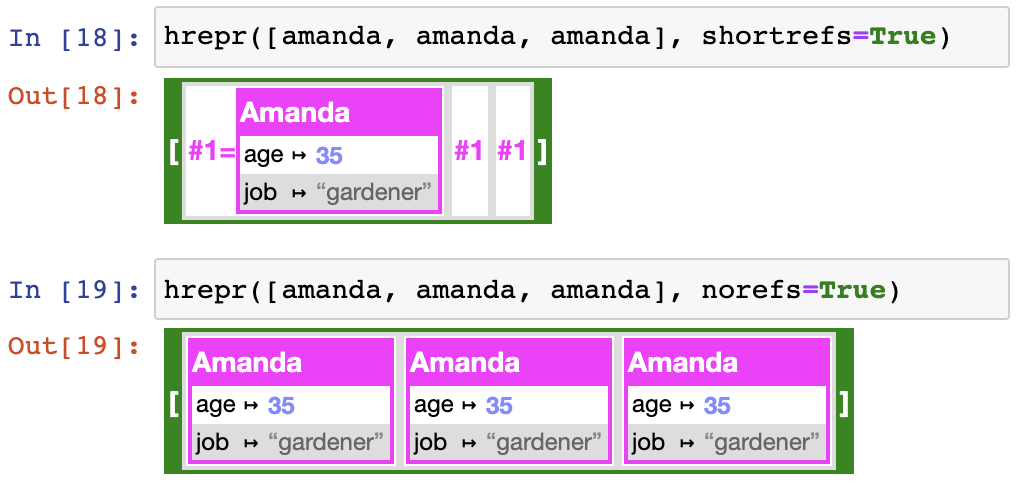

The shortrefs and norefs configuration keys control the representation of references:

norefs is ignored when there are circular references.

Generate HTML using the H parameter to __hrepr__, or import it and use it directly:

from hrepr import H

html = H.span["bear"](

"Only ", H.b("YOU"), " can prevent forest fires!",

style="color: brown;"

)

print(html)

# <span class="bear" style="color: brown;">Only <b>YOU</b> can prevent forest fires!</span>H can be built incrementally: if you have an element, you can call it to add children, index it to add classes, and so on. For instance:

from hrepr import H

html = H.span()

html = html("Only ")

html = html(style="color: brown;")["bear"]

html = html(H.b("YOU"), " can prevent forest fires!")

print(html)

# <span class="bear" style="color: brown;">Only <b>YOU</b> can prevent forest fires!</span>This can be handy if you want to tweak generated HTML a little. For example, hrepr(obj)["fox"] will tack on the class fox to the representation of the object.

hrepr.make.instance(title, fields, delimiter=None, type=None): formats the fields like a dataclass, with title on top.hrepr.make.bracketed(body, start, end, type=None): formats the body with the specified start/end bracket.

The J function lets you create JavaScript expressions. If an expression takes an HTML element as an argument, you can create one and pass it along with the returns() statement, which tells hrepr to insert it where the J() expression is located.

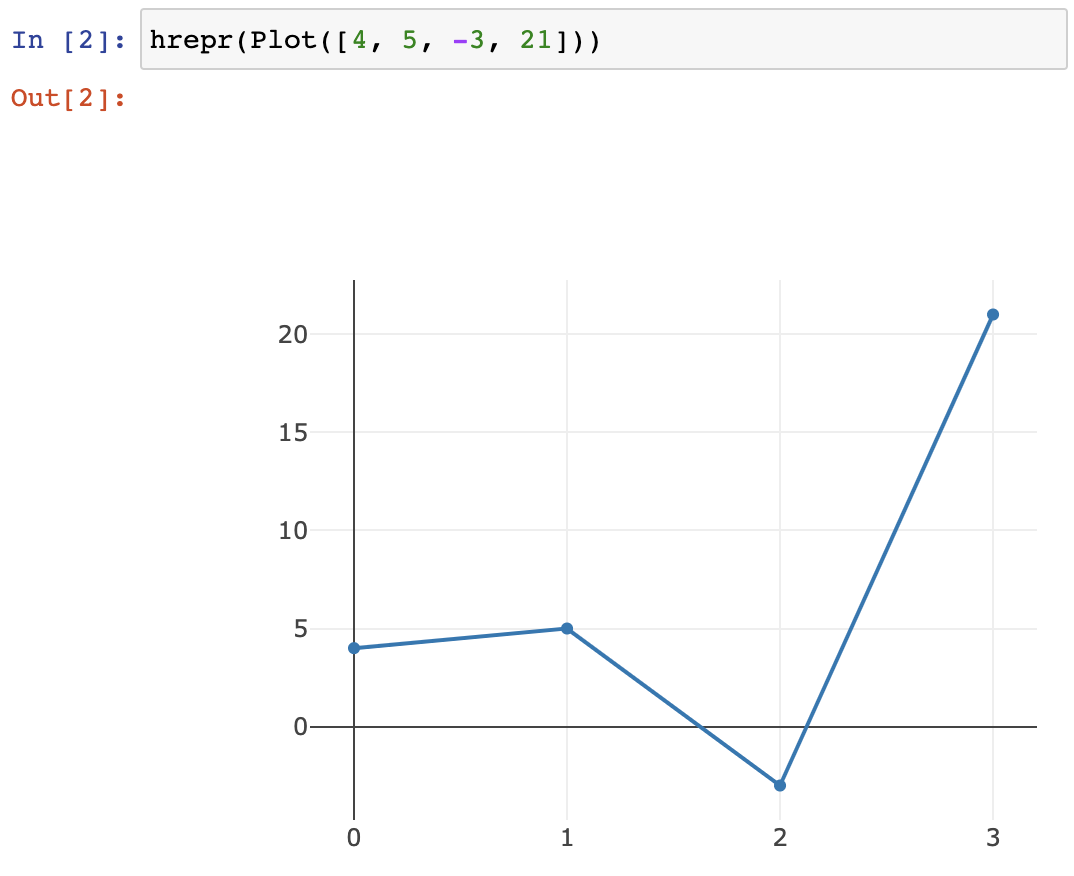

For example, you can load Plotly and create a plot like this:

from hrepr import H, J, returns

def plot(data):

Plotly = J(src="https://cdn.plot.ly/plotly-latest.min.js").Plotly

return Plotly.newPlot(

returns(H.div()),

[{"x": list(range(len(data))), "y": list(data)}],

)

print(plot([math.sin(x / 10) for x in range(100)]).as_page())The above will:

- Put the specified script in the

<head>element of the page (hence why you need theas_page()call for it to work). - Insert some hrepr library code.

- Insert a

<div>, as specified inreturns(H.div()), where theJ()call is, with an auto-generated ID. - Get the

Plotly.newPlotfunction in the global namespace. - Call it with the

divelement as the first argument, and any other arguments given (as long as they can be serialized to JSON).

It will look like this:

You can, of course, nest J inside H, e.g. H.body(H.h1(...), H.div(J(...))), as much as you'd like, so you can easily combine multiple libraries. Note that if a JavaScript has no returns() argument, it may to return some HTML element to insert in its stead (a placeholder will be created automatically).

Be careful with J objects: since they override __getattr__ and __call__, they will almost never raise exceptions and it is easy to accidentally generate improper expressions.

Another example, this time using ESM (modules):

cystyle = [{"selector": "node","style": {"background-color": "#800", "label": "data(id)"},},{"selector": "edge","style": {"width": 3,"line-color": "#ccc","target-arrow-color": "#ccc","target-arrow-shape": "triangle","curve-style": "bezier"}}]

cytoscape = J(module="https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/cytoscape/3.23.0/cytoscape.esm.min.js")

j = cytoscape(

container=returns(H.div(style="width:500px;height:500px;border:1px solid black;")),

elements=[

{"data": {"id": "A"}},

{"data": {"id": "B"}},

{"data": {"id": "C"}},

{"data": {"source": "A", "target": "B"}},

{"data": {"source": "B", "target": "C"}},

{"data": {"source": "C", "target": "A"}},

],

style=cystyle,

layout={"name": "cose"},

)

print(j.as_page())The above will work like the previous example, with the following differences:

- Import the specified module.

- All keyword arguments are packed into an object, which will be passed as the last (in this cas, only) argument to the module's default export.

If you wish to use a non-default export, use namespace= instead of module=. For example, if you want to use the JavaScript import import {fn} from "xxx", use J(namespace="xxx").fn(...).

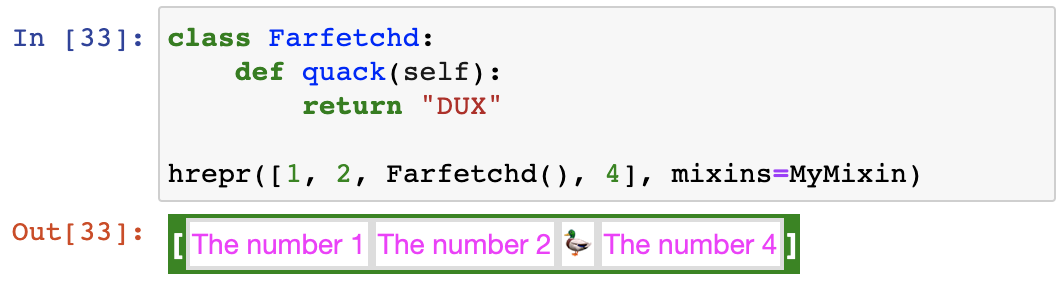

If you want to really customize hrepr, you can use mixins. They look like a bit of black magic, but they're simple enough:

# ovld is one of the dependencies of hrepr

from ovld import ovld, extend_super, has_attribute, OvldMC

from hrepr import hrepr

class MyMixin(metaclass=OvldMC):

# Change the representation of integers

@extend_super

def hrepr_resources(self, cls: int):

# Note: in hrepr_resources, cls is the int type, not an integer

return self.H.style(".my-integer { color: fuchsia; }")

@extend_super

def hrepr(self, n: int):

return self.H.span["my-integer"]("The number ", str(n))

# Specially handle any object with a "quack" method

def hrepr(self, duck: has_attribute("quack")):

return self.H.span("🦆")The annotation for a rule can either be a type, ovld.has_attribute, or pretty much any function wrapped with the ovld.meta decorator, as long as the function operates on classes. See the documentation for ovld for more information.

And yes, you can define hrepr multiple times inside the class, as long as they have distinct annotations and you inherit from Hrepr. You can also define hrepr_short or hrepr_resources the same way.

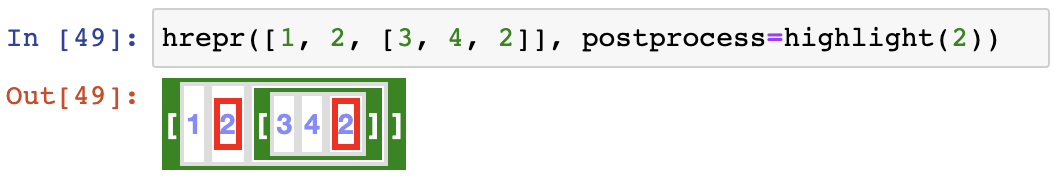

hrepr can be given a postprocessor that is called on the representation of any object. You can use this to do things like highlighting specific objects:

from hrepr import H

style = H.style(".highlight { border: 3px solid red !important; }")

def highlight(x):

def postprocess(element, obj, hrepr):

if obj == x:

# Adds the "highlight" class and attaches a style

return element["highlight"].fill(resources=style)

else:

return element

return postprocess

hrepr([1, 2, [3, 4, 2]], postprocess=highlight(2))To put this all together, you can create a variant of hrepr:

hrepr2 = hrepr.variant(mixins=MyMixin, postprocess=highlight(2))

hrepr2([1, 2, 3]) # Will use the mixins and postprocessorAlternatively, you can configure the main hrepr:

hrepr.configure(mixins=MyMixin, postprocess=highlight(2))But keep in mind that unlike the variant, the above will modify hrepr for everything else as well.