When you implement agent-based models, you need to specify the order in which the attributes of the agents are updated. There are different ways you can define the order, and the choice of the method for updating can have important implications on the results of the model. We will discuss the main updating techniques.

A simple approach for agent-based models is synchronous updating. Here all agents are calculated for time step t using the information of all the cells in time step t-1. If one has N agents, then the order in which these N agents are updated is not relevant since only information of the previous time step is used.

In most real systems updating of information is not synchronous. Instead it looks more like a continuous process where some agents make decision earlier than others. This is what we call asynchronous updating. Now the order in which the N agents are updated becomes important. Suppose you update the states of agent i and agent j. Since decisions of agent j depends on the states of agent i, and visa versa, one may derive different decisions when first agent i is updated and then agent j, or the other way around. Therefore, one distinguishes different orders.

One can use a fixed order of updating. For example, you may update agent 1 up to N always in the same order. This can lead to artifacts. Suppose agents are looking for resources, and agent 1 always has the first choice, and agent N the last. This will definitely favor agent 1.

Due to this artifact, which might be undesirable, a common approach is random asynchronous updating. Each time step, agents are updated in a random order. This leads to the case that sometimes agent 1 is updated before agent N, and sometimes agent N before agent 1. Each agent gets equal opportunities on average due to the random order of updating.

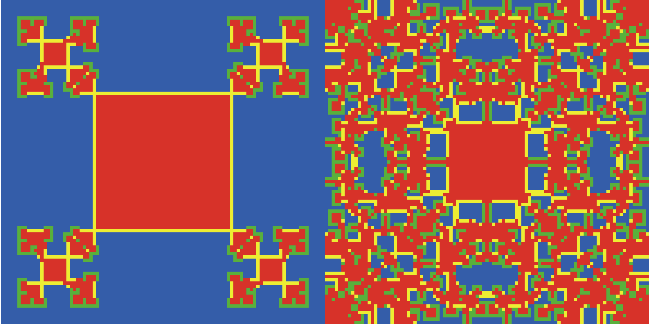

An example of the importance of updating is illustrated by the model of spatial games of Martin Nowak and Robert May (1992). They developed a spatial model where the environment is a 99x99 square lattice with fixed boundaries. Each cell represents an agent who plays rounds of a Prisoner’s Dilemma game with its eight surrounding neighbors. Each round an agent has to decide to play C (cooperate) or D (defect) against all eight neighbors. The payoff of the Prisoners Dilemma is 1 when an agent and her neighbor cooperate, and b>1 when the agent defects while the neighbor cooperates. In the other two cases, mutual defection and cooperation by the agent and defection by the neighbor, leads to a zero payoff. The sum of all games played with the neighbors is the total payoff for the agent. If agents chose only what is in their best interest they would always defect. But we will see that in this spatial game there are situation in which cooperation emerges. The way the model updates the agents affect the results, and that is why it is a good example to show the importance of how agents are updated.

At the beginning of each step the agent will copy the best strategy of the eight neighboring agents. When one starts with all cooperators, except the agent in the center, you will derive interesting patterns of cooperators and defectors (Figure 7). Cooperation and defection can coexist in a spatial setting.

Figure 7: Spatial patterns of cooperators and defectors. The color of the cell relates to strategy of the agent during the last 2 time steps. The cell is red when D follows a D, is blue when C follows a C, is green when D follows a C, and is yellow when C follows a D. The figures above are two snapshots of spatial patterns when the initial screen is all cooperative, except a defector in the center of the screen. (t about 20, and t about 100)

Figure 7: Spatial patterns of cooperators and defectors. The color of the cell relates to strategy of the agent during the last 2 time steps. The cell is red when D follows a D, is blue when C follows a C, is green when D follows a C, and is yellow when C follows a D. The figures above are two snapshots of spatial patterns when the initial screen is all cooperative, except a defector in the center of the screen. (t about 20, and t about 100)

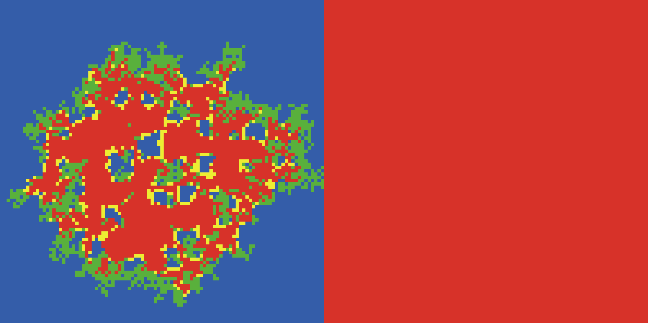

Huberman and Glance (1993) criticized the findings of Nowak and May (1992) by showing that the results are sensitive to the way information is updated. When agents do not update their strategies all at the same time, but asynchronously, the defector strategy will spread rapidly (Figure 8). Hence changing the updating from synchronous to asynchronous leads to a stable solution of all defection.

Figure 8: Spatial patterns when updating is asynchronous.

Figure 8: Spatial patterns when updating is asynchronous.

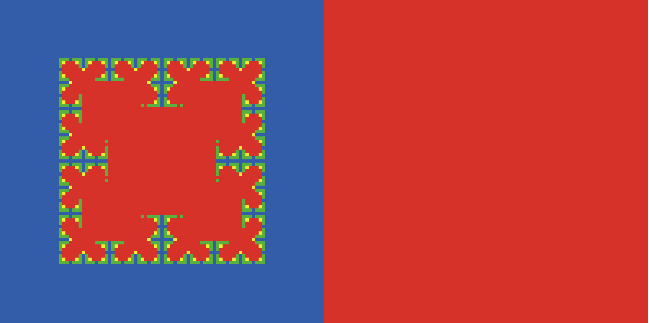

There are a number of other sensitivities we can show with this model. Nowak and May (1992) used a neighborhood of eight neighbors and the agent itself for determining the score and assumed that agents would also play a game against their own strategy. Thus the score is the results of 9 games. Playing a game against your own strategy is a questionable assumption. Suppose we assume that the score is only determined by 8 games against the neighbors, thus excluding a game against one’s own strategy. In that case, defectors will start dominating too (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Spatial patterns when updating is synchronous and agents do not play games against themselves.

Figure 9: Spatial patterns when updating is synchronous and agents do not play games against themselves.

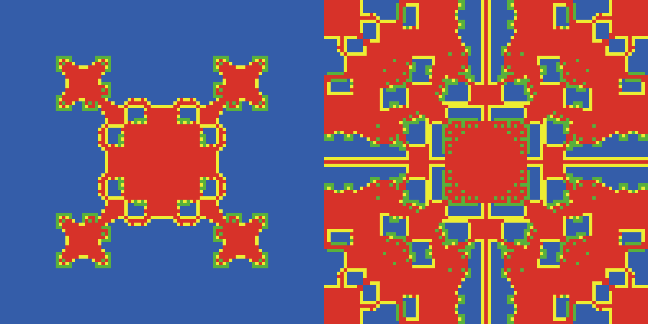

Finally, we show the results in the case where agents determine the score of the 9 games against neighbors and their own strategy, but they do copy the strategy of the best 8 neighbors, even when their own strategy is better. This leads to a co-existence of cooperation and defection strategies (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Spatial patterns when updating is synchronous but agents imitate always the best neighbor, even when this neighbor has not a better payoff.

Figure 10: Spatial patterns when updating is synchronous but agents imitate always the best neighbor, even when this neighbor has not a better payoff.

NETLOGO EXAMPLE: SPATIAL VARIATIONS

Model: Right click on the Link and Save it. Open Netlogo and Run it with NetLogo.