An overview of the important facts in the Apple vs. FBI case, including post-case technical & legal concerns

- What is the history behind Apple's compliance with law enforcement?

- What are important factors in legal precedent(s) for the future?

- The Post-Case Investigation

- The Burr-Feinstein Encryption Bill

- Post-AppleVsFBI Encryption Panels & Committees

- On December 2nd, 2015, Syed Rizwan Farook and his wife Tashfeen Malik killed 14 people and injured 22 at the Inland Regional Center in California during a San Bernardino County Department of Public Health training session/ party. They were pursued by police and died hours later in a shoot-out. The iPhone at the center of this case, a 5C with iOS9, was found by law enforcement in a Black Lexcus IS300 (see lines 23-4 of pgs 4-5).

- The phone was the property of Farook's employer, the San Bernardino County Department of Public Health. It had been issued to Farook for work & the County still retained official ownership of the phone at the time of the attack (see lines 22-24 of pg 6), but for some reason had neglected to install mobile-device management software which was standard on their government-issued work phones & would have enabled the IT department to remotely unlock the device when needed without user assistance.

"If that particular iPhone was using MobileIron, the county's IT department could unlock it," MobileIron Vice President Ojas Rege told Reuters... If it had been, the high stakes legal battle that has pitted Apple and much of the technology industry against the U.S. government could have been avoided altogether.

- The FBI claimed this phone was used to communicate with his wife and/ or future victims (see lines 16-18 of pg 6), not with other terrorists. Farook is believed to have used other private phones for that, two of which were found destroyed behind their residence (see lines 1-4 pg 22 or pg 4 of Pluhar's declaration).

- Through accessing Farook's account, the last date the FBI had been able to obtain in the iCloud backup data was October 19th 2015 (see top of pg 11 or line 12 of pg 22), as iCloud data on Apple's servers is not protected by the user's iPhone passcode. The FBI stated that Farook changed his iCloud password & disabled the iCloud automatic-backup feature on October 22nd; Jonathan Ździarski (iOS digital forensics expert) argued it was unlikely to be intentional since the Find-My-iPhone feature was still enabled, among other factors.

Find my iPhone is still active on the phone (search by serial number), so why would a terrorist use a phone he knew was tracking him? Obviously he wouldn’t. The Find-my-iPhone feature is on the same settings screen as the iCloud backup feature, so if he had disabled backups, he would have definitely known the phone was being tracked. But the argument that Farook intentionally disabled iCloud backup does not hold water, since he would have turned off Find-my-iPhone as well. --Jonathan Ździarski @JZdziarski

"Apple engineers saw iCloud backup auth was failing. This tells me FBI seized the phone powered up, and royally blew it turning it off." --Jonathan Ździarski @JZdziarski

- Ździarski outlined amateur forensics practice mistakes that could have been made when, & after, the phone was confiscated; principle among them: turning the iPhone off if it was still on, which would lock it. He also raised the important question of why (or if) the victim's phones weren't searched, since they would have copies of the communications the FBI seeks (his full take on the case here). He was among the iPhone security experts who submitted an “amici curiae" brief through The Center for Internet and Society (see Techdirt's full list of amici curiae briefs submitted so far, with analysis). The FBI contradicted the claim made by Apple engineers & Supervisory Special Agent Christopher Pluhar said "Farook's iPhone was found powered off" (see pg 29 lines 7-17 or pg 2 lines 7-17). Ździarksi said "the best way to determine if the device truly was off or not is to release the carrier’s tower records showing last activity."

- A "senior Apple executive" (one of many who apparently spoke with journalists on a Friday call) claimed that the Apple ID password linked to the iPhone was changed within 24 hours of the phone being confiscated. This executive only came forward, and thus far remained anonymous, because they "had thought it was under a confidentiality agreement with the government. Apple seems to believe this agreement is now void since the government brought it up in a public court filing." The FBI's motion to compel Apple confirmed the passcode was reset while in government custody and blamed it on Farook's employer in the San Bernardino Department of Health (see footnotes on pg 18).

However San Bernardino County argued they had reset the password at the FBI's request.

"The County was working cooperatively with the FBI when it reset the iCloud password at the FBI's request."

- In an inquiry to San Bernardino County CAO David Wert, he shared a statement from Laura Eimiller (FBI Press & Public Relations at U.S. Department of Justice) which confirmed that the County did not "independently conduct analysis" but that "the FBI worked with [them] to reset the iCloud password on December 6th," which (as previously stated in the footnotes on pg 18 here) meant Apple was unable to assist with the auto-backup function on the iPhone. However, unless journalists seriously misquoted the Apple senior executives (who have yet to be personally named), this contradicted their statement that the change was made within 24 hours. This inquiry also showed that the FBI did not know "whether an additional iCloud backup to the phone after that date -- if one had been technically possible -- would have yielded any data." Their reason for pursuing Apple under the All Writs Act order was that they believe there might be "more data [on the iPhone] than an iCloud backup contains," which also contradicts Apple's assertion that had they not reset the iCloud password/ Apple ID, this case would not be necessary. The pieces of "device-level data" the FBI wanted to access from the phone itself included the keyboard cache (see pg 29 line 22); the claim that there was more keyboard cache data in the device than on the iCloud backup is disputed by Ździarski here. Likewise, San Bernardino Police Chief Jarrod Burguan has said "there is a reasonably good chance that there is nothing of any value on the phone."

-

Farook's employer consented to a law enforcement search of the device (see lines 22-24 of pg 6).

-

The government filed their ex parte application & released their first Order to assist on February 16th; Apple said they were not contacted about it directly beforehand but were instead given notice through the press in conjunction with the public (see footnotes on pg 11).

- On February 22nd, the Pew Research Center released a survey conducted Feb. 18-21 among 1,002 American adults (varying by age, education, political identity, and smartphone ownership) where they asked whether Apple should unlock the San Bernardino suspect’s iPhone to aid the FBI’s ongoing investigation. Overall, 51% of Americans said Apple should unlock the iPhone; 38% said they should not unlock it; the remaining 11% did not offer an opinion either way. When separated based on their political identity, "almost identical shares of Republicans (56%) and Democrats (55%) say that Apple should unlock the San Bernardino suspect’s iPhone. By contrast, independents are divided: 45% say Apple should unlock the iPhone, while about as many (42%) say they should not unlock the phone." The results were a bit more divided among non-partisan Independents, with "unlock" still being favored. When separated based on education, there was no definitive trend between less- or more-educated, though difference of opinion was greatest among those with "some college" education: 34% said Apple should not unlock the iPhone while 56% said they should. Those in the "some college" education group also had the highest percentage of them support unlocking the iPhone (56%) compared to other levels of education. When separated based on age, the older the respondent was, the more likely it was they would support unlocking the iPhone or offer no opinion. When separated based on smartphone ownership, respondents were more likely to be against Apple unlocking the iPhone if 1) they owned a smartphone 2) their smartphone was an iPhone.

- The US House of Representatives Committee on the Judiciary held a session to discuss this court case on March 1st, with FBI Director James Comey, Apple Senior Vice President Bruce Sewell, Professor Susan Landau (co-author of "Privacy On The Line: The Politics of Wiretapping and Encryption"), & New York County District Attorney Cyrus R. Vance Jr. as witnesses. "The Encryption Tightrope: Balancing Americans' Security & Privacy" is available on YouTube (I also have a local .mp4 copy in case it is taken down). Responding to Congressman Deutch during the hearing, Comey remarked:

"Slippery slope arguments are always attractive, but I suppose you could say, 'Well, Apple's engineers have this in their head, what if they're kidnapped and forced to write software?' That's why the judge has to sort this out, between good lawyers on both sides making all reasonable arguments."

- On March 3rd, Microsoft and fourteen other tech companies filed an amicus curiae brief together in support of Apple. San Bernardino County District Attorney Michael Ramos also filed an amicus curiae brief but in support of the FBI, which is still being mocked for speculating about a "lying-dormant cyber pathogen endangering San Bernardino County's infrastructure" on the iPhone (see pg 3 or 6/40). Jeremiah Grossman, founder of White Hat Security, has created the webpage www.cyberpathogen.com displaying the quote & linking to Ździarski's article on the document.

- On March 4th, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein released a statement on the case leaning in Apple's favor, expressing concern for the safety of citizens as well as "human rights defenders, civil society, journalists, whistle-blowers and political dissidents" in authoritarian countries who would likely demand more access upon seeing the FBI successfully compel Apple.

- On March 21st, one day before the scheduled hearing, the Department of Justice announced in a filing that it wanted to postpone or possibly cancel the hearing, claiming that "an outside party demonstrated to the FBI a possible method for unlocking Farook's iPhone" (see pg 3). It was not stated who that outside party is, though The Intercept says the Department of Justice told reporters they don't work for the government. The DOJ and FBI jointly contracted a New Jersey vendor of the Israel-based company Cellebrite (which manufactures data extraction & analysis devices for phones) on the same day. Reuters says the Tel Aviv national daily newspaper Yedioth Ahronoth (in Hebrew) reported two days later that the contract was indeed part of the San Bernardino investigation. Neither the US government nor Cellebrite have commented on the nature of the partnership. Emily Chang, host of Bloomberg West, soon claimed that the request was accepted by the judge, which was confirmed by a record of a telephonic conference & subsequent filing in reply (see the last page). The government was required to file a status report on April 5th 2016 after two weeks of testing this new method, at which time either a new date would have been set or the trial cancelled altogether. The method that was being tested is believed to be some variation of the NAND copying / mirroring technique.

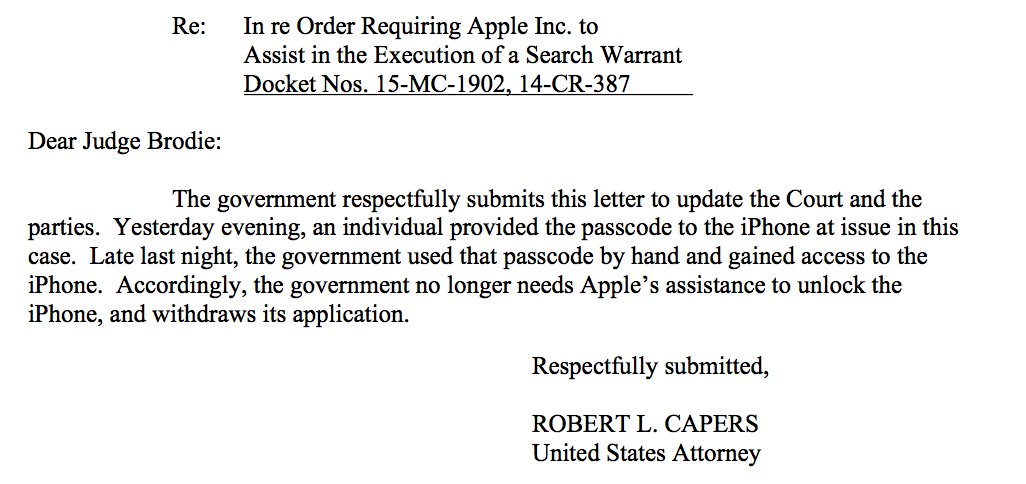

- On March 28th, the government filed a status report requesting that the order compelling Apple to assist the FBI be vacated because they had "now successfully accessed the data stored on Farook’s iPhone and therefore no longer require[d] the assistance from Apple" (see here). The request was accepted the following day, effectively ending the case in San Bernardino; however several other cases are still ongoing and Apple used the outcome of this case to argue that the government hasn't demonstrated their assistance to be necessary (see pg 1 or 10/55). On April 22nd, that case in New York ended with the government filing another application to vacate the order since "an individual provided the passcode to the iPhone at issue in this case. Late last night, the government used that passcode by hand and gained access to the iPhone."

- "The FBI is currently reviewing the information on the phone, consistent with standard investigatory procedures," said Department of Justice public affairs director Melanie Newman. The method used, and the identity of the "outside party," have still not been made public. However, on the same day, the DOJ and FBI jointly signed another purchase order contract with suspected third-party Cellebrite for "Information Technology Supplies" valued at $218,000. Based on contracting records from 2008-2016, where the majority are valued between $3,000-20,000, this is their most expensive contract (the second most expensive being a Feb 21st 2014 purchase order for communications equipment at $120,000).

The FBI was demanding Apple build a custom mobile iOS with two standard passcode security features disabled: the 10-try limit & escalating time delays (see pg 2).

Note: Court filings & articles refer to the custom mobile iOS by different names, most commonly 'GovtOS' & 'FBiOS'. For the purposes of consistency to avoid confusion, this overview will use 'FBiOS.'

The 10-try limit wipes an iPhone's data after 10 attempts. The time-delays feature will wait 1 minute after four incorrect passcode entries before it accepts another attempt, subsequently increasing to 5 minutes, 15 minutes, and finally 1 hour. Bypassing these features would have allowed the FBI to perform a brute-force attack, where they could guess the passcode as many times & as fast as the iPhone firmware will allow, without destroying the data. Along with disabling these security features, the FBI also wanted the custom iOS to allow them to enter the 10,000 possible passcode combinations electronically instead of by hand (which would have been incredibly slow comparatively). This would have likely been done through Device Firmware Upgrade (DFU) mode, normally used for restoration by installing a fresh iOS version when an iPhone fails to boot.

However, the FBI could have technically built this custom iOS on their own (though it would take more time). The one thing they actually needed was for Apple to sign FBiOS using their developer software key, because only software signed with this key will be accepted by SecureRom's signature checker (though jailbreakers have found bugs in the past which let them bypass this).

So the 'encryption' we were dealing with was a matter of authentication.

Authentication falls under one of the three principles of information security (CIA): accessibility. Authentication deals with how you prove you hold authorization to carry out specific operations, like accessing an account. This is something you know (eg. a password), something you have (eg. a card), or something you are (eg. biometrics).

Authentication is also an element of cryptography, but distinct from privacy/ confidentiality (see the Purpose section of Gary C. Kessler's "An Overview of Cryptography").

The San Bernardino phone was locked with a 4-digit PIN. PINs, unlike passwords (which can be alphanumeric & longer), are numeric and usually very short (4-6 numbers allowed on average). Even if you had a PIN and a password of the same length, it would probably take more time to break the password with brute-force.

Therefore, if the FBI used FBiOS, authenticated by Apple's software key/ digital signature, it would have been able to run on Farook's phone and broken the PIN within 24 hours.

The definition of a backdoor is something which bypasses normal authentication. Or, more (perhaps too) broadly:

backdoor: A design fault, planned or accidental, that allows the apparent strength of the design to be easily avoided by those who know the trick -- Newton's Telecom Dictionary: 28th Updated & Expanded Edition

What should be highlighted here is that Apple claimed not to be able to, or at least not want to, access their customer's data. Apple customers have an expectation of confidentiality (the first information security principle) even from Apple itself. Apple does not position itself as a party with access to encrypted communications on customer phones. If this is true, why is there a threat to encryption?

If the FBI was compelling someone who was a party or key-holder to encrypted communications, then it would be more accurate to say that they were “breaking encryption” by taking advantage of a social engineering weakness which, at the present time, exists with the majority of encryption use.

The problem was that the 'encryption' is already broken. Quoting from what a "senior Apple executive" said to Buzzfeed, Apple's fear that they have been asked to "create a sort of master key" is misleading at best, because Apple was not asked to create a key but rather use the master key they already possess in conjunction with a custom iOS that lacked two security features.

Thus, in the sense that the word is being used in the media, the ‘backdoor’ already exists. The ‘key to all locks’ is Apple’s private signing key. --Liam Kirsh @choicefresh

Firefox founder Blake Ross offered a very well-written & humorous take on how security holes fail us, in both our digital & non-digital lives, and says this debate was about whether "a private company [should] be allowed to sell unbreakable security."

To be clear: Contrary to a lot of shoddy reporting, and some rather “generous” language from Apple, this is not the world we’re living in yet. The fact that Apple can break into your phone demonstrates that we’re still firmly in “Coke recipe” territory.

Leif Ryge from Ars Technica explained why being a single point of failure is the bigger issue industry-wide:

How did we get here? How did so many well-meaning people build so many fragile systems with so many obvious single points of failure?

I believe it was a combination of naivety and hubris. They probably thought they would be able keep the keys safe against realistic attacks, and they didn't consider the possibility that their governments would actually compel them to use their keys to sign malicious updates.

Fortunately, there is some good news. The FBI is presently demonstrating that this was never a good assumption, which finally means that the people who have been saying for a long time that we need to remove these single points of failure can't be dismissed as unreasonably paranoid anymore.

... So when Apple says the FBI is trying to "force us to build a backdoor into our products," what they are really saying is that the FBI is trying to force them to use a backdoor which already exists in their products. (The fact that the FBI is also asking them to write new software is not as relevant, because they could pay somebody else to do that. The thing that Apple can provide which nobody else can is the signature.)

Is it reasonable to describe these single points of failure as backdoors? I think many people might argue that industry-standard systems for ensuring software update authenticity do not qualify as backdoors, perhaps because their existence is not secret or hidden in any way. But in the present Apple case where they are themselves using the word "backdoor," abusing their cryptographic single point of failure is precisely what the FBI is demanding.

Todd Weaver, founder & CEO of Purism, says the focus of the case avoided "the larger issue of control."

You don’t actually own your phone. If we truly owned our phones, court ordered warrants would be served directly to the owner of the phone. The warrants in the case of Apple v FBI were served to Apple, who actually has control of your phone.

... If Apple loses this legal battle, all phones, tablets, and computing devices that are under the control of a company are then legally bound to comply with a warrant to give up the key that controls your device. If Apple, or any organization, controls your device, you are giving your legal rights over to that organization.

Apple is being pursued because contrary to their commendable implimentation of 'strong encryption,' they retain the ability to backdoor their products, not only through allowing the use of PINs but because they are a centralized point of failure in regards to building proprietary firmware & software.

"If Apple gets to call #FBiOS a 'backdoor,' I suggest we refer to 'Apple updates' as 'official backdoor only good guys are allowed to use.'" --Pwn All The Things @pwnallthethings

Note: iPhones can be set to manual (requires user authentication, ie. passcode) or auto-update. During the update process, iPhone updates are individually signed per-device on Apple's servers, which would prevent an attacker from downgrading to an insecure version.

However, there can also be security benefits from Apple's proprietary approach -- assuming that Apple remains trustworthy. Mashable's Senior Tech Correspondent Christina Warren wrote a detailed article outlining iPhone security and encryption features.

And it's here where Apple has an inarguable advantage, especially when compared to other phone makers and operating system makers.

Apple controls the whole stack, including updates, which means that it can push out updates and bug fixes very quickly.

This is not how the rest of the mobile industry works. Consider the situation with Stagefright, an Android vulnerability disclosed last year. Even though Google was very quick to patch the exploit, it took considerable time for those updates to get down the chain to non-Nexus devices. Millions of devices will never get an update against that vulnerability.

Consider this point made by Dan Froomkin & Jenna McLaughlin of The Intercept:

You might say we’re entering the Post-Crypto phase of the Crypto Wars.

Think about it: The more we learn about the FBI’s demand that Apple help it hack into a password-protected iPhone, the more it looks like part of a concerted, long-term effort by the government to find new ways around unbreakable encryption — rather than try to break it. [emphasis added]

The Electronic Frontier Foundation published a few pieces on this case and offered only passing criticism of Apple on this point, even though they included passages like this:

Would it be easy for Apple to sign the requested cracking software? The answer any trained security engineer will give you is "it shouldn't be."

... There are pros and cons to this approach, but Apple considers this signing key among the crown jewels of the entire company. There is no good revocation strategy if this key is leaked, since its corresponding verification key is hard-coded into hundreds of millions of devices around the world.

It shouldn't be easy, but it's still possible. Disabling security features in so many devices also shouldn't be easy, but it's possible and, considering Apple's response, a very real problem.

Ray Dillinger framed the FBI's court order in a rather interesting way: as a dramatic & unfriendly bug report.

Taking all of this into consideration:

- Was Apple being asked to "create" a "backdoor"? Unless you consider Apple creating a custom iOS, signed with their special software key, to be outside the bounds of 'normal' in terms of software authentication powers they already possessed, the answer is no. Remember that Apple could use this capability at any time, regardless of whether it's compelled or not. If you interpret 'normal' authentication to not include Apple's abilities and consider that 1) Apple disabling security features in their OS is an out-of-the-ordinary procedure for them & 2) though now weakly grounded, most Apple customers did have an expectation of confidentiality... then it could be argued that this was "creating a backdoor." I think that, whether or not this was a backdoor, a further distinction should be made on whether they were going to be 'using' one or 'creating' one -- as such a fact is very important to Apple feeling enough pressure to increase iPhone security. You can read Jonathan Ździarski's "Three-Prong Backdoor Test" (read the formal explanation here), EFF's thought-piece on the historical definition of backdoors or another argument on this from the technical perspective by Brandon Edwards (note that I did not make my argument depend on it being limited to one device, which this article focused on & disputed).

A backdoor is a component of a security mechanism, in which the component is active on a computer system without consent of the computer’s owner, performs functions that subvert purposes disclosed to the computer’s owner, and is under the control of an undisclosed actor.

- Was Apple being ordered to "break encryption"? Again, this still depends on your interpretation of the previous question. The encryption system of the iOS 9 itself was not being broken; security features dealing with how authentication is proven were. Brute-force attacks are a hack of security vulnerabilities, not an encryption backdoor.

Therefore, it would be rather more accurate to say the FBI was demanding that Apple take advantage of system security vulnerabilities which already existed.

It is now known that Apple has the ability to backdoor their own products & could be compelled to use that backdoor.

Initially some security experts argued that this backdoor wouldn't work on iPhones newer than 5C due to the Secure Enclave firmware, a co-processor of many independently-functioning kernels within the A7 64-bit system chip which stores keys in supposedly tamper-resistant hardware & also uses secure boot to ensure that all software installed on the OS is signed by Apple (remember authentication from earlier). On February 19th, a “senior Apple executive” told journalists at Motherboard, The Guardian and others that this was not true – the FBiOS "would be effective on every type of iPhone currently being sold."

Apple included this warning in an FAQ for customers:

Law enforcement agents around the country have already said they have hundreds of iPhones they want Apple to unlock if the FBI wins this case. In the physical world, it would be the equivalent of a master key, capable of opening hundreds of millions of locks. Of course, Apple would do our best to protect that key, but in a world where all of our data is under constant threat, it would be relentlessly attacked by hackers and cybercriminals. As recent attacks on the IRS systems and countless other data breaches have shown, no one is immune to cyberattacks.

"Hundreds of millions of locks." This would have applied to most, if not all, of their customer base.

This detail is very important, if true, because many tech journalists (including from Ars Technica) also speculated that FBiOS wouldn't even work on other 5C iPhones because, since the FBI allowed that the custom software could have been tied specifically to the phone's unique identifier, it should be limited to this one device.

A description of the Unique Identifier (UID) can be found on page 59 of Apple's iOS Security Whitepaper:

A 256-bit AES key that’s burned into each processor at manufacture. It cannot be read by firmware or software, and is used only by the processor’s hardware AES engine. To obtain the actual key, an attacker would have to mount a highly sophisticated and expensive physical attack against the processor’s silicon. The UID is not related to any other identifier on the device including, but not limited to, the UDID.

Because the UID is "baked into its hardware," Ars Technica editor Peter Bright said that this request made the assumption that the UID could be extracted, which appears to be a difficult process.

Difficulty of extraction aside, he did offer that it might be possible to swap identifiers to apply to other 5C phones.

Therefore, Apple may not only have admitted that Secure Enclave is not secure enough but that it would be possible to swap identifiers in this custom OS. This probably had something to do with the fact that Apple could force an update to Secure Enclave without wiping the data.

EFF's Joseph Bonneu said the following in relation to whether Secure Enclave protects newer phones:

(Older devices that lack the secure enclave also apply a similar delay, but apparently do so from within the operating system.) It's possible, though not completely clear from Apple's documentation, that a software update would be able to modify this behavior; if not, this would completely prevent Apple from enabling faster passcode guessing on newer devices.

There has been further speculation that the secure enclave could refuse to accept any software update (even one signed by Apple) unless unlocked by entering the passcode, or alternately, that a software update on a locked phone would erase all of the cryptographic keys, effectively making the phone's storage unreadable. Apple's security documentation makes no such guarantees, though, and there are indications that this isn't the case. So special cracking tools from Apple could potentially still modify the secure enclave's behavior to remove both the 10-guess limit and the delays between guesses.

This means that, if leaked, FBiOS could have been used on any iPhone.

What was also not confirmed by Apple was whether a strong password (not a PIN) remains a safeguard against this attack. Against a brute-force attack, a long & complex password should work under normal circumstances (taking months to many years to break). Micah Lee, a technologist at the The Intercept, said it would:

It’s true that ordering Apple to develop the backdoor will fundamentally undermine iPhone security, as Cook and other digital security advocates have argued. But it’s possible for individual iPhone users to protect themselves from government snooping by setting strong passcodes on their phones — passcodes the FBI would not be able to unlock even if it gets its iPhone backdoor.

...The short version: If you’re worried about governments trying to access your phone, set your iPhone up with a random, 11-digit numeric passcode.

Note that he advises even an 11-digit numeric (numbers only) passcode would be sufficient, though alphanumeric (numbers, characters, and symbols) is stronger because it increases the amount of possible combinations. With a "truly random" 11-digit passcode, it would have taken an average of 127 years to crack even with FBiOS (note: the following graphs are maximum time estimates, not averages).

Drawing from page 12 of Apple's iOS Security White Paper (iOS 9.0 or later), this is due to limitations on how the brute-force attack can be performed:

The passcode is entangled with the device’s UID, so brute-force attempts must be performed on the device under attack. A large iteration count is used to make each attempt slower. The iteration count is calibrated so that one attempt takes approximately 80 milliseconds. This means it would take more than 5½ years to try all combinations of a six-character alphanumeric passcode with lowercase letters and numbers.

However, these figures only apply if Secure Enclave or another aspect of the iPhone's security architecture wasn't also being breached as well, such as the "Effaceable Storage" processor (contains the CPU, BootROM, RAM, crypto engines, Apple's public signing key, and the UID key). Daniel Kahn Gillmor, technologist for the ACLU, wrote a piece on how you could bypass the auto-erase security feature on an iPhone 5C, without destroying the data, by copying the flash memory of the file system key stored in this processor:

The FBI can simply remove this chip from the circuit board (“desolder” it), connect it to a device capable of reading and writing NAND flash, and copy all of its data. It can then replace the chip, and start testing passcodes. If it turns out that the auto-erase feature is on, and the Effaceable Storage gets erased, they can remove the chip, copy the original information back in, and replace it. If they plan to do this many times, they can attach a “test socket” to the circuit board that makes it easy and fast to do this kind of chip swapping.

If the FBI doesn't have the equipment or expertise to do this, they can hire any one of dozens of data recovery firms that specialize in information extraction from digital devices.

NAND flash storage is an extremely common component. It's found in USB thumb drives, mobile phones, portable music players, low-end laptops—pretty much every portable device. Desoldering a chip from the circuitboard is straightforward enough that there are many clips on YouTube showing the practice, and reading and writing a bare NAND chip requires a minor investment in hardware and training that the FBI has probably already made.

The Washington Post claimed an anonymous FBI official told them that "the bureau was aware of this method early on and concluded that it wouldn’t work, for technical reasons." However, as the government has classified both the third-party and the "new method" they brought forth, this comment may have been made just to deflect attention.

If the government decides to regularly use its password-bypassing technique in criminal trials, it risks making the method public every time defense attorneys and courts ask questions about how it is accessing information on a locked device.

The law does allow the government to present sensitive sources and methods under seal – out of the view of the public and, more importantly, Apple. But that protection isn’t a guarantee. And like any secret, the more people know, the less likely it is to stay secret.

Apple attorneys said on Monday they would push the government to reveal the nature of their tactic if it is used at trial, though it is unclear what legal mechanism they would have to do so.

Ździarski, after consulting with other tech experts, believes the FBI is most likely using this method, a portion of which he demonstrated himself using a jailbreak.

Using a NAND copying / mirroring technique, this barrier could be overcome in iOS 9, allowing the device to write and verify the attempt, but have that change later blown away by restoring an original copy of the chip. They wouldn’t have to copy the whole NAND in this case. If they can isolate the part of the chip that is written to (even though it’s encrypted), they can just keep writing over that portion of the chip. If the methods from iOS 8 were borrowed for this, then it could be partially automated by entering the pin through the USB, as well as using a light sensor to determine which pin successfully unlocked the device

He also says that "with the info that experts have come forward with, I am reasonably confident FBI themselves, with current talent, could get into this phone."

With this in mind, a very valuable & proactive thing Apple could do is recommend that their customers upgrade their passwords, especially by moving away from numeric PINs to alphanumeric passwords (as the level of protection provided by each is different). iPhone device passwords on iOS9 can be changed through the following steps:

Find the

Settingsicon. Scroll to the redTouch ID & Passcodeoption. You will be prompted to enter your current passcode. Once you have done so, scroll down toChange Passcode(underTurn Passcode Off). You will be prompted to enter a new passcode. Before entering anything, selectPasscode Optionsand chooseCustom Alphanumeric Code.

Until now Apple has given their customers a false sense of security, allowing them to use short passcodes & PINs. The last line of protection should be a strong password, which is under the user's control to change, not a security feature which can apparently be disabled.

To understand the legal history behind this case in terms of the US government ordering Apple to "unlock" iPhones, I recommend this clarifying article by TechCrunch's Matthew Panzarino: "No, Apple Has Not Unlocked 70 iPhones For Law Enforcement." The most important lines are about the difference between decryption and extraction:

There are two cases involving data requests by the government which are happening at the moment. There is a case in New York [which] ...involves an iPhone running iOS 7. On devices running iOS 7 and previous, Apple actually has the capability to extract data, including (at various stages in its encryption march) contacts, photos, calls and iMessages without unlocking the phones. That last bit is key, because in the previous cases where Apple has complied with legitimate government requests for information, this is the method it has used.

It has not unlocked these iPhones — it has extracted data that was accessible while they were still locked.

The California case, in contrast, involves a device running iOS 9. The data that was previously accessible while a phone was locked ceased to be so as of the release of iOS 8, when Apple started securing it with encryption tied to the passcode, rather than the hardware ID of the device... So Apple is unable to extract any data including iMessages from the device because all of that data is encrypted.

In short: extraction allows them to access unencrypted data on iOS 7 or older; because they have implimented passcode-based encryption in iPhones running iOS 8 or iOS 9, this data is no longer accessible through extraction. Therefore this request was different compared to Apple's history of compliance, which the government's arguments never acknowledged (in fact, they argued the opposite). [Find citation for this claim]

Regardless of whether this specific piece of custom software would have been useable on other devices, Apple says that they were already getting similar requests to do so now that it has been shown they have the capability. This puts them in a position where they would either save FBiOS in the event of future cases, or safely destroy it & then be forced to spend more time/ resources recreating it in the future (see pg 3).

The government says: “Just this once” and “Just this phone.” But the government knows those statements are not true; indeed the government has filed multiple other applications for similar orders, some of which are pending in other courts. And as news of this Court’s order broke last week, state and local officials publicly declared their intent to use the proposed operating system to open hundreds of other seized devices—in cases having nothing to do with terrorism.

If this order is permitted to stand, it will only be a matter of days before some other prosecutor, in some other important case, before some other judge, seeks a similar order using this case as precedent. Once the floodgates open, they cannot be closed, and the device security that Apple has worked so tirelessly to achieve will be unwound without so much as a congressional vote.

I saw over and over again the comment that the legal precedent(s) this case could have set carries more risk than the technical risk posed by FBiOS. FBI Director James Comey already admitted that legal prescedent would be established with this case, as happens with all cases; therefore it should not have been cast aside as hypothetical hysteria. Since I am not a lawyer, I am not familiar with the specific statutes that were being considered, but here are some of the main points summarized:

- This court order would have forced Apple to code a custom iOS which deliberately took advantage of security vulnerabilities in their authentication systems. If “code is speech," then speech (here in the form of code) can be compelled. While this was a different form of compelled speech, compelled speech is not at all new. It is still an open question of who exactly at Apple could have been compelled to do this, whether anyone would have complied at all...

Apple employees are already discussing what they will do if ordered to help law enforcement authorities. Some say they may balk at the work, while others may even quit their high-paying jobs rather than undermine the security of the software they have already created, according to more than a half-dozen current and former Apple employees. Among those interviewed were Apple engineers who are involved in the development of mobile products and security, as well as former security engineers and executives.

... The fear of losing a paycheck may not have much of an impact on security engineers whose skills are in high demand. Indeed, hiring them could be a badge of honor among other tech companies that share Apple’s skepticism of the government’s intentions. “If someone attempts to force them to work on something that’s outside their personal values, they can expect to find a position that’s a better fit somewhere else,” said Window Snyder, the chief security officer at the start-up Fastly and a former senior product manager in Apple’s security and privacy division.

Apple said in court filings last month that it would take from six to 10 engineers up to a month to meet the government’s demands. However, because Apple is so compartmentalized, the challenge of building what the company described as “GovtOS” would be substantially complicated if key employees refused to do the work.

...and whether prior precedent of "code is speech" applied, since the case of Bernstein vs. US Department of Justice was about the publication of code (read Park Higgins' EFF piece on "code is speech" related to 3-D printing). Before Apple had put forth a reply outlining how their defense would argue, at least one of Apple's objections to the court order was projected to be on First Amendment grounds:

In Apple's fight to knock down a court order requiring it to help FBI agents unlock a killer’s iPhone, the tech giant plans to argue that the judge in the case has overreached in her use of an obscure law and infringed on the company’s 1st Amendment rights, an Apple attorney said Tuesday.

Theodore J. Boutrous -- one in a pair of marquee lawyers the technology company's has hired to wage its high-stakes legal battle -- outlined the arguments Apple plans when it responds to the court order this week.

[...] “The government here is trying to use this statute from 1789 in a way that it has never been used before. They are seeking a court order to compel Apple to write new software, to compel speech," Boutrous said in a brief interview with The Times.

Boutrous said courts have recognized that the writing of computer code is a form of expressive activity -- speech that is protected by the 1st Amendment.

This was confirmed in Apple's first motion against the FBI's court order on February 25th, in addition to objections on Fifth Amendment due-process grounds (see pgs 32 & 34 respectively). It is important to note with regards to passwords that biometric methods (ie. the iPhone's Touch ID fingerprint scanner), unlike character passwords, is a grey area currently treated as not protected under the Fifth Amendment and can be legally compelled. While the protection for memorised passwords under the Fifth Amendment has often been challenged, many courts still distinguish between physical keys and 'contents of the mind.'

Neil Richards, one of the law professors supporting Apple, said furthering the precedent of "code is speech" may carry unwanted consequences:

Where does this leave us, then, when we’re considering the regulation of code by the government? The right question to ask is whether the government’s regulation of a particular kind of code (just like regulations of spending, or speaking, or writing) threatens the values of free expression. Some regulations of code will undoubtedly implicate the First Amendment. Regulations of the expressive outputs of code, like the content of websites or video games, have already been recognized by the Supreme Court as justifying full First Amendment treatment. It’s also important to recognize that as we do more and more things with code, there will be more ways that the government can threaten dissent, art, self-government, and the pursuit of knowledge.

But on the other hand, and critically, there are many things that humans will do with code that will have nothing to do with the First Amendment (e.g., launching denial of service attacks and writing computer viruses). Code = Speech is a fallacy because it would needlessly treat writing the code for a malicious virus as equivalent to writing an editorial in the New York Times. Similarly, if companies use algorithms to discriminate on the basis of race or sex, wrapping those algorithms with the same constitutional protection we give to political novels would needlessly complicate civil rights law in the digital age.

Another counter-point from David Golumbia (Associate Professor at Virginia Commonwealth University) to the "code is speech" argument is that, while often containing elements of speech, code more aptly fits into the category of 'action' because it executes.

This is most easily seen when we think about the main use to which code is put. The reason we have and pay so much attention to code is because it is executed. Execution is not primarily a form of communication, not even between humans and machines. Execution is the running of instructions: it is the direct carrying out of actions. It is adding together two numbers, or multiplying ten of them, or looping back to perform an operation again, or incrementing a value. This is what code does. Lots of code does not even look like language at all—it looks, if anything, like giant arrays of numbers that mean very little to anyone but the most highly-trained programmer. All of it executes, or at least can be executed. That is what it is for. That is what it does. That’s what makes it different from lots of other things, like most language and expressive media, all of whose primary function is to convey thoughts and ideas and feelings between persons.

The Department of Justice objected to Apple's First Amendment argument for the following reasons (see pgs 32-34):

"...it does not involve a person being compelled to speak publicly, but a for-profit corporation being asked to modify commercial software that will be seen only by Apple." [pg 32 lines 13-15]

"[T]hat [programming] occurs at some level through expression does not elevate all such conduct to the highest levels of First Amendment protection." [pg 32 lines 19-20]

"To the extent Apple’s software includes expressive elements — such as variable names and comments — the Order permits Apple to express whatever it wants, so long as the software functions.. the Order’s 'broad requirements' do 'not dictate any specific message.'" [pgs 32-33 lines 24-1]

"And even assuming, arguendo, that the Order compels speech-like programming, there is no audience: Apple’s code will be developed in the utmost secrecy and will never be seen outside the corporation." [pg 33 lines 3-5]

"Apple will respond that if it modifies Farook’s iPhone to allow the government access to the phone, it “could be viewed as sending the message that [it] see[s] nothing wrong with [such access], when [it] do[es]... It is extremely unlikely that anyone could understand Apple to be expressing a message of hostility to 'data security and the privacy of citizens'..." [pg 34 lines 1-11]

Addressing the argument that Apple's "speech" would not be protected due to lack of audience, Apple argued that the presence of an audience has never been a requirement for protected speech (see footnotes on pg 23):

- US Congressman Ted Lieu (D-Los Angeles County), one of the Congressmembers who put forth a bill for the ENCRYPT ACT (full text here), issued this statement regarding the Apple court order on February 17th:

"This court order also begs the question: Where does this kind of coercion stop? Can the government force Facebook to create software that provides analytic data on who is likely to be a criminal? Can the government force Google to provide the names of all people who searched for the term ISIL? Can the government force Amazon to write software that identifies who might be suspicious based on the books they ordered?"

- If a telecommunications provider can be compelled to take advantage of a security flaw undermining encryption for its customers, then they will be compelled. This will put pressure on other businesses to either comply or build their products so that they are not a centralized authority of proprietary software (a factor which, even with end-to-end encryption, will leave them vulnerable to shutdowns as was the case with WhatsApp). Security technologist Bruce Schneier warned the precedent may motivate the government to limit what sorts of security features tech companies can offer customers in order to maintain the ability to compel them. However some are already going ahead with either dumping or encrypting sensitive customer information, though they're hesitating to advertise that they're doing so (both to avoid attention on their currently-deficient privacy measures and potential hostility from governments). "... Many start-ups that wouldn't have considered it before the Apple FBI fight are now doing so and discussing the accompanying trade-offs." Though Apple has not released public plans to do so, the "senior executives" have indicated they want to increase encryption implimentation in their products:

- Other countries pay attention to the US on surveillance policy. Though Apple has not said they hold this fear, lawyers and security experts say this would create a threat to foreign customers & tech businesses as well. If the U.S. government can compel Apple to take advantage of a security vulnerability, why can't others? A recent example they cite is where FBI Director James Comey called for encryption backdoors & the Chinese government introduced new counter-terrorism laws a few weeks later.

From Reuters, "Obama Sharply Criticizes China's Plans for New Technology Rules":

In an interview with Reuters, Obama said he was concerned about Beijing's plans for a far-reaching counterterrorism law that would require technology firms to hand over encryption keys, the passcodes that help protect data, and install security 'backdoors' in their systems to give Chinese authorities surveillance access.

Sounds oddly familiar, doesn't it?

To be sure, Western governments, including in the United States and Britain, have for years requested tech firms to disclose encryption methods, with varying degrees of success.

Officials including FBI director James Comey and National Security Agency (NSA) director Mike Rogers publicly warned Internet companies including Apple and Google late last year against using encryption that law enforcement cannot break.

Beijing has argued the need to quickly ratchet up its cybersecurity measures in the wake of former NSA contractor Edward Snowden's revelations of sophisticated U.S. spying techniques.

- The use of the All Writs Act is not uncommon in surveillance cases -- in fact, the ACLU mapped more than 63 cases of law enforcement using it to compel tech companies into helping them access customer data; the states with the most cases are California (16) and New York (12). Jonathan Mayer's "Assistance for Current Surveillance: The All Writs Act" explains the legality of its use. However its legitimacy in retrospective surveillance is being challenged. In response to President Obama's request for "moderation" in this debate, Susan Crawford, professor of law & public policy, explains how CALEA (Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act) will limit the FBI's legitimacy in compelling Apple:

The problem for the president is that when it comes to the specific battle going on right now between Apple and the FBI, the law is clear: twenty years ago, Congress passed a statute, the Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act (CALEA) that does not allow the government to tell manufacturers how to design or configure a phone or software used by that phone — including security software used by that phone.

CALEA was the subject of intense negotiation — a deal, in other words. The government won an extensive, specific list of wiretapping assistance requirements in connection with digital communications. But in exchange, in Section 1002 of that act, the Feds gave up authority to “require any specific design of equipment, facilities, services, features or system configurations” from any phone manufacturer. The government can’t require companies that build phones to come to it for clearance in advance of launching a new device. Nor can the authorities ask a manufacturer to design something new — like a back door — once that device is out.

Judge James Orenstein, in another Apple iPhone-unlocking case from the Eastern District of New York, also disputed the use of AWA in regards to whether Apple could be considered 'close' to the crime (see pgs 1, 29 31-32, & 40 respectively):

"For the reasons set forth below, I conclude thatunder the circumstances of this case,the government has failed to establish either that the AWApermits the relief it seeks or that, even if such an order is authorized, the discretionary factors I must consider weigh in favor ofgranting the motion."

-

It was highly unlikely that the FBI did not have alternative means to access the phone or its data in conjunction with the National Security Agency (NSA) or private data forensics companies, as they have a history of mutual cooperation. Legally, alternative means would have impacted the legitimacy of using the All Writs Act, as EFF explained: "This point is potentially relevant legally, as cases interpreting the All Writs Act require 'an absence of alternative remedies.' However, we lack firm evidence that the FBI has such a capability. Apple also probably doesn't want to argue that its phone is insecure so the authorities should just break into it some other way." Now that they have cancelled the trial, despite their prior repeated assertions that unlocking the iPhone was only possible with Apple's assistance, many are wondering whether the FBI had prior knowledge of this capability and/or only changed course for strategic reasons, such as realizing their arguments were weak. This case was valuable in promoting the 'national security vs. encryption' false dichotomy so that public pressure may make it easier to compel companies under similar circumstances in the future.

-

San Bernardino County has a history of partnering with the FBI on work with little respect for privacy. In July 2016, The Verge revealed that they were... "one of the most productive nodes in a nationwide iris-scanning project, collecting iris data from at least 200,000 arrestees over the last two and a half years... San Bernardino’s activity is part of a larger pilot program organized by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, one that began as a simple test of available technology but has quietly grown into something far more ambitious. Since its launch in 2013, the program has stockpiled iris scans from 434,000 arrestees, an FBI spokesperson confirmed." They were able to collect so many scans, the majority of which came from California, through "information-sharing agreements with other agencies, including US Border Patrol, the Pentagon, and local law enforcement departments." Despite usually being required to submit privacy reports on projects involving personal data, the FBI has so far bypassed that after a preliminary privacy review in 2014 determined they were not necessary because the scope of the project was so small at the time.

FBI [Associate Deputy Director] David Bowdich said in a statement Monday night [March 28th] that the agency "cannot comment on the technical steps that were taken to obtain the contents of the county-issued iPhone, nor the identity of the third party that came forward as a result of the publicity generated by the court order."

"During the past week, to include the weekend, extensive testing of the iPhone was done by highly skilled personnel to ensure that the contents of the phone would remain intact once technical methods were applied. The full exploitation of the phone and follow-up investigative steps are continuing," Bowdich added. "My law enforcement partners and I made a commitment to the victims of the 12/2 attack in San Bernardino and to the American people that no stone would be left unturned in this case. We promised to explore every investigative avenue in order to learn whether the San Bernardino suspects were working with others, were targeting others, or whether or not they were supported by others."

"While we continue to explore the contents of the iPhone and other evidence, these questions may not be fully resolved, but I am satisfied that we have access to more answers than we did before and that the investigative process is moving forward," he said. -- ABC News Radio

More than a week after they claimed to have access to the iPhone, they still claimed to be analyzing it. Ździarski says this is beyond the normal timespan in which incriminating content is discovered on iPhones.

“We’re now doing an analysis of that data, as we would in any other type of criminal terrorism investigation,’’ said James Baker, the FBI’s general counsel, on Tuesday [April 5th at Global Privacy Summit 2016, a conference of the International Association of Privacy Professionals]. “That means we would follow logical leads.” As a result, he says it’s “simply too early” to know whether the iPhone at the heart of the San Bernardino investigation is going to be useful.

After more than two weeks of analyzing the iPhone's contents, the FBI had still not released any news of whether they found important evidence.

A law enforcement source tells CBS News that so far nothing of real significance has been found on the San Bernardino terrorist's iPhone, which was unlocked by the FBI last month without the help of Apple.

It was stressed that the FBI continues to analyze the information on the cellphone seized in the investigation, senior investigative producer Pat Milton reports.

On April 19th, the FBI finally said that they had found nothing of importance on the iPhone: no evidence of the use of encrypted communications, no evidence of contact with another plotter or anyone associated with ISIS, and even no evidence of contact with friends or family. CNN, Daily Mail, and Associated Press oddly treated this news as an important revelation of new data, even though it is a lack of data and apparently only comprised an 18-minute time period which was missing from the iCloud data they had already accessed.

Hacking the San Bernardino terrorist's iPhone has produced data the FBI didn't have before and has helped the investigators answer some remaining questions in the ongoing probe, U.S. law enforcement officials say.

They claim the FBI is still analyzing the data. However the chances of finding anything significant has long passed.

The method used to access the iPhone is still the real mystery. "According to two people with direct contact," a team of Cellebrite engineers led by a hacker in Seattle managed to unlock/ access the phone, and "'everyone at the company has since been forced to sign non-disclosure agreements to remain silent about the matter.'" John McAfee claimed to supposedly have knowledge of a specific contract from the summer of 2013 between Cellebrite and the FBI for a mobile forensics device called the UFED Touch. None of the publicly available contracts specifically mention UFED Touch (they describe the cateogry of devices, not names), so McAfee's evasiveness on divulging sources is odd considering his claim is entirely possible and could have reinforced his view of why the FBI went after Apple:

Why would the FBI bother to get caught up in a battle with Apple if they already had a solution to unlock the iPhone? McAfee says the FBI was less interested in Apple than it was in precedent. If it won against Apple, then it could go to Google and get a master key into Android — which has 91% of the world market. A software master key — which costs nothing, can be given to every agent in the DOJ for free. The Cellebrite devices costs thousands of dollars per unit — way above the DOJ budget for everyday use.

Two anonymous law enforcement officials, "speaking on condition of anonymity, told CNN the 'outside party' was not Cellebrite." National security reporters from The Washington Post also believe Cellebrite's involvement is merely "widely rumored" based on statements (from more officials refusing to give their names) responding to "the bureau [being] peppered with inquiries from state and local law enforcement officials seeking to know whether the solution might be useful for their cases," which they are hesitant to answer as they don't want tech companies to fix whatever vulnerability they're exploiting. Based on talking to "people familiar with the matter," they claim the third-party helpers were just "professional hackers" who discovered an iOS 9 zero-day flaw, with no mention of any company or group affiliation. The outlet continues to chide those who think it was most likely Cellebrite which, based on their lack of clear sourcing, is a rather bold move. It could easily be the case that both stories are correct, that the mastermind "professional hacker" was independently contracted by Cellebrite to aid their team of engineers, or vice versa that the FBI hired the hacker and then the Cellebrite team provided him with the tools purchased through the contract with the DOJ and FBI. Ździarski said that the FBI hiring a completely independent hacker would be "inconsistent with Comey’s past statements of purchasing from a professional company with a reputation of protecting IP."

It would also bring up the question of why the "one-time fee" contract with the independent professional hacker was not made public through the Federal Procurement Data System (FPDS) like the others. About six minutes into the first Aspen Security Forum London talk titled "The Complexities of Today's Security Challenges" on April 21st, Comey said that the amount the FBI spent to unlock the iPhone was "more than I will make in the remainder of this job, which is seven years and four months, for sure"." Based on calculating the sum from public records of his executive salary (around $183,000 annually, though it appears to increase to $185,100 for 2016), the cost must be at least $1.3 million (see pg 6). His talk is available through The Aspen Institute on YouTube. "Several U.S. government sources" told Reuters that the amount was less than $1 million; their most interesting claim however was that "not even Comey knows who it is," which would again contradict his earlier claim when he said he knew "a fair amount about them" & his more recent claim that he had a "good sense" of the identity of the the third-party contractor.

On January 12th 2017, Motherboard reported they had obtained over 900Gb of hacked custmer & device data from Cellebrite, who soon put out a press release that they were notifying their customers about the breach. The data showed that the company is popular with a number of authoritarian regimes as well as U.S. federal and state law enforcement, including the FBI and Secret Sevice.

Other companies contracted during the pre-trial period for similar products and services include Black Bag Technologies (purchase orders from 2016), Magnet Forensics (purchase orders from 2016) and technical support from Novetta (purchase orders from 2016).

Besides the NAND mirroring technique, another method possibily being used by the FBI is the "IP Box" tool, which "latches onto a susceptible iPhone's power circuitry and enters PINs over USB."

The so-called "IP Box" tested by security consultancy MDSec works by entering a PIN over USB, then immediately cutting power to the iOS device before the attempt is recorded. This has the effect of eliminating the 10-try limit, at the expense of significant time lost to iOS device reboots.

MDSec places the time per attempt at nearly 40 seconds. While this long interval may seem likely to discourage brute force attempts in all but a few scenarios, research suggests that more than 25 percent of the population use one of 20 similar PINs, potentially cutting the mean time to crack a PIN down to minutes.

Additionally, such tools are readily available over the internet, with some models costing as little as $175.

As the firm notes, this appears to be an automated method to exploit a flaw described last November in CVE-2014-4451. Apple patched that bug in iOS 8.1.1, but older iOS versions remain vulnerable.

So unless the FBI's third-party helper found a new vulnerability in the software, this device wouldn't work on the San Bernardino iPhone.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation has challenged the government on its policy for hiding vs. publicly disclosing security vulnerabilities in information technologies ('Vulnerabilities Equities Process' or VEP), so they may be required to disclose the method in the near future. Amy Hess, the witness for the FBI at the Energy and Commerce encryption panel on April 19th, told New York Times they only "purchased the method from an outside party so that we could unlock the San Bernardino device... [but] did not, however, purchase the rights to technical details about how the method functions, or the nature and extent of any vulnerability upon which the method may rely in order to operate." The FBI may be trying to avoid that disclosure process by claiming they "don’t have sufficient knowledge of the vulnerability to implicate the process."

The government’s decision simply to hire the locksmith and ignore how that lock was opened “creates a gap in the review process” that is “not transparent and has not been set in legislation,” [Denelle Dixon-Thayer, chief legal and business officer at Mozilla], said.

The F.B.I.’s carefully worded statement reveals that law enforcement authorities have found a loophole in the vulnerability review process created by the administration— hire the hacker to extract the data, but be careful to not know how he got the job done.

“The F.B.I. is intentionally exploiting a known vulnerability and enabling people to profit off of it,” said Alex Rice, the chief technology officer at HackerOne, a security company in San Francisco that helps coordinate vulnerability disclosure for corporations. “The collateral damage done by this lack of transparency and the possible ongoing existence of the flaw is serious.”

Though if true, by claiming they know too little about the device the FBI would be admitting that they recklessly ignored best practices in forensic science and "created an extremely dangerous situation for all of us":

Best practices in forensic science would dictate that any type of forensics instrument needs to be tested and validated. It must be accepted as forensically sound before it can be put to live evidence. Such a tool must yield predictable, repeatable results and an examiner must be able to explain its process in a court of law. Our court system expects this, and allows for tools (and examiners) to face numerous challenges based on the credibility of the tool, which can only be determined by a rigorous analysis. The FBI’s admission that they have such little knowledge about how the tool works is an admission of failure to evaluate the science behind the tool; it’s core functionality to have been evaluated in any meaningful way. Knowing how the tool managed to get into the device should be the bare minimum I would expect anyone to know before shelling out over a million dollars for a solution, especially one that was going to be used on high-profile evidence.

A tool should not make changes to a device, and any changes should be documented and repeatable. There are several other variables to consider in such an effort, especially when imaging an iOS device. Apart from changes made directly by the tool (such as overwriting unallocated space, or portions of the file system journal), simply unlocking the device can cause the operating system to make a number of changes, start background tasks which could lead to destruction of data, or cause other changes unintentionally. Without knowing how the tool works, or what portions of the operating system it affects, what vulnerabilities are exploited, what the payload looks like, where the payload is written, what parts of the operating system are disabled by the tool, or a host of other important things – there is no way to effectively measure whether or not the tool is forensically sound. Simply running it against a dozen other devices to “see if it works” is not sufficient to evaluate a forensics tool – especially one that originated from a grey hat hacking group, potentially with very little actual in-house forensics expertise.

Nonetheless they have started to inform members of Congress, beginning with Dianne Feinstein & Richard Burr:

According to a new report in National Journal, the FBI has already briefed Senator Dianne Feinstein (D-CA) on the methods used to break into the iPhone at the center of Apple's recent legal fight. Senator Richard Burr (R-NC) is also scheduled to be briefed on the topic in the days to come. Feinstein and Burr are both working on a new bill to limit the use of encryption in consumer technology, expected to be made public in the weeks to come.

I can't access National Journal content as a non-subscriber. Here are screenshots from those who could.

From C|Net:

The National Journal said both Feinstein and Burr believe Apple shouldn't be given information on how the FBI broke into the phone, which is an obvious stance given the bill they're planning to introduce as soon as this week.

Feinstein, among a chorus of many politicians, called encryption "the Achilles' heel in the internet" during a Face The Nation broadcast following the 2015 Brussels terror attack -- despite no evidence to suggest encryption played any role in the operation. ("...Encryption is arguably closer to Achilles' shield than his heel"). Burr, a Republican senator for North Carolina, recently announced that he "look[ed] forward to working with Mr. [Donald] Trump."

On September 14th, Cambridge University security researcher Sergei Skorobogatov published a paper titled "The Bumpy Road Towards iPhone 5c NAND Mirroring." It was a proof-of-concept summary of a "successful hardware mirroring process" of the iPhone 5c which showed "it was possible to bypass the limit on passcode retry attempts." Contrary to the FBI previously insisting this attack wasn't feasible, the paper demonstrated that "any sufficiently skilled hardware hacker could have accessed Farook’s phone with less than $100 in equipment."

On September 16th, three U.S. media organisations (The Associated Press, USA TODAY, and VICE Media) jointly filed a FOIA request against the FBI regarding records on the tool used to break into Farook's iPhone. The complaint was shared publicly by USA TODAY investigative reporter Brad Heath, who also indicated that all three media groups had previously filed individual FOIA requests to the FBI and that they had all been denied (see pgs 9-12 for details).

More specifically, through this action, the News Organizations seek to compel the FBI to provide records of the publicly-acknowledged business transaction that resulted in the purchase this March of the so-called iPhone access tool.

In October, the FBI claimed they had obtained the iPhone of Dahir Adan, who stabbed ten people in a Minnesota mall on September 17th. Many have remarked that this investigation may go the same way as the San Bernardino case, since the phone was locked with a passcode and they are "still trying to figure out how to gain access to the phone’s contents."

Thornton didn’t say in the press conference what model iPhone Adan owned or what operating system the device ran. Both are key factors in whether the FBI will be able to get past its security measures. That’s because beginning with iOS 8 in 2014, iPhones and iPads have been encrypted such that not even Apple can decrypt the device’s contents, even when police or FBI serve a warrant to the company demanding its help.

... FBI Agent Thornton told Thursday’s press conference that the bureau had “analyzed more than 780 gigabytes of data from multiple computers and other electronic devices” in its investigation of Adan. “We are conducting an extensive review of his social media and other online activity,” he said. “We continue to review his electronic media and digital footprint.”

The Department of Justice may also take advantage of fingerprint databases in order to bypass iPhones locked using biometric data. In a recently released court filing from May, they sought "authorization to depress the fingerprints and thumbprints of every person who is located at the SUBJECT PREMISES during the execution of the search," as well as "access devices" such as passwords or encryption keys, for a Lancaster, California property, without specifying in the warrant who or what they were looking for.

On January 6th 2017, the Justice Deparatment responded to the lawsuit from The Associated Press, USA TODAY, and VICE Media by releasing "close to 100 pages" of heavily redacted documents, revealing "almost nothing" about how the FBI broke into the iPhone. One paragraph states that the FBI received "at least three inquiries" from companies who were interested in providing them with an exploit tool.

In March 2018, the Justice Department released an oversight report regarding the FBI's conduct, especially their Operational Technology Division (OTD), during the Bernardino investigation. There were concerns of "inadequate communication and coordination," especially that Hess and Comey may have given "inaccurate testimony to Congress on the FBI’s capabilities," though they "found no evidence that OTD had the capability to exploit the Farook iPhone at the time of then-Director Comey’s Congressional testimony and the Department’s initial court filings."

Through a staff leak it was revealed that both Feinstein and Burr were drafting a bill, titled the "Compliance with Court Orders Act of 2016," which would require all companies to be able to give the government any communications data in an unencrypted format, effectively banning them from offering any encryption software to users for which that service does not possess a decryption key, particularly end-to-end. The Intercept said the senators "told reporters they were still working on the draft and couldn’t comment on the language of an unfinished version." The draft was officially released on April 13th and indirectly confirmed that the leaked draft from April 7th was authentic.

Interestingly, the term "backdoor" was not used even once in the document, even though that is exactly what would need to be implemented while at the same time trying to maintain any semblance of cybersecurity. The extent of those backdoors is potentially broad, to even involve deleted or destroyed data.

The section Design Limitations was especially misleading, as it doesn't take into account that many systems implement encryption as a fundamental design feature (see lines 6-9 pg 4).

The entities affected by this legislation included "a device manufacturer, a software manufacturer, an electronic communication service, a remote computing service, a provider of wire or electronic communication service, a provider of a remote computing service, or any person who provides a product or method to facilitate a communication or the processing or storage of data" (see lines 18-25 pg 6). According to tweets from The Hill's cybersecurity reporter Cory Bennett, who uploaded the bill's draft, senators were still saying as of the bill's release on April 7th that they didn't know about the FBI briefing them on the iPhone hack, implying that Feinstein and Burr may have been the only ones informed.

From Softpedia:

In case you’re wondering how come Feinstein is getting access to such information, she is the vice chairman of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence and one of the senators who backed regulations that would force phone manufacturers to install backdoors for government access on devices sold in the United States.

In addition to Feinstein, Senator Richard Burr also got access to similar information. He’s also one of the backers of pro-backdoor bills and together with Feinstein, took FBI’s side in the case against Apple, emphasizing that the agency shouldn’t tell Cupertino how it unlocked the San Bernardino iPhone.

“I don't believe the government has any obligation to Apple. No company or individual is above the law, and I'm dismayed that anyone would refuse to help the government in a major terrorism investigation,” Feinstein was quoted as saying.

From Apple Insider:

Saying that whatever method was used by the FBI will have a "short shelf life," Apple on Friday [April 8th] revealed it has no intention to sue the bureau in an effort to find out how it hacked the iPhone 5c used by a terrorist in California.

The majority of security experts came out against the bill. Matt Blaze, computer scientist director for The Distributed Systems Laboratory at the University of Pennsylvania (also featured in the John Oliver's Last Week Tonight episode), called it "worse than [the] Clipper [chip]," which he is credited for breaking. Matthew Green, cryptographer and professor at Johns Hopkins University, said it "is pretty much as clueless and unworkable as I expected it would be." Nate Cardozo, Senior Staff Attorney for EFF, said it "would outlaw secure communications & storage, endanger security, & endanger US business. And it'd be unconstitutional."

According to The Register, security technologist Bruce Schneier said the bill was so broad that it would even outlaw file compression algorithms.

He pointed out that it isn't just cryptographic code that would be affected by this poorly written legislation. Schneier, like pretty much everyone, uses lossy compression algorithms to reduce the size of images for sending via email but – as it won't work in reverse and add back the data removed – this code could be banned by the law, too. Files that can't be decrypted on demand to their original state, and files that can't be decompressed back to their exact originals, all look the same to this draft law.

Julian Sanchez, a policy analyst and technology journalist for the Cato Institute, provided a lengthy explanation of basic browser operations that would be outlawed and required changes by this bill, notably session key generation for HTTPS connections.