| title | author | publish_on | type | canonical_url | image | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Astronomers and Engineers Use a Grid of Computers at a National Scale to Study the Universe 300 Times Faster |

NRAO |

|

user |

|

Data Processing for Very Large Array Makes Deepest Radio Image of the Hubble Ultra Deep Field

The Universe is almost inconceivably vast. So is the amount of data astronomers collect when they study it. This is a challenging process for the scientists and engineers at the U.S. National Science Foundation’s National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO). But what if they could do it over 300 times faster?

The NRAO manages some of the largest and most used radio telescopes in the world, including the NSF’s Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA). When these telescopes are observing the Universe, they collect vast amounts of data, for hours, months, even years at a time, depending on what they are studying. “We made a single deep image of a small portion of the sky with nearly 2 Terabytes of data – equivalent to 1350 photos taken with a phone every day for 2 years. There are other projects that use the VLA to collect many 100s of Terabytes of data!”, explains Sanjay Bhatnagar, a scientist at the NRAO leading the Algorithms R&D Group. “Traditional ways of processing this data can take months or even years to finish – much longer than most existing supercomputing centers are optimized for.”

Looking for a more efficient way to process a particularly large VLA data set, to produce one of the deepest radio images of the Hubble Ultra Deep Field (HUDF), made famous by the Hubble Telescope, NRAO staff decided to try a different approach. “Earlier attempts using CPU cores in a supercomputer center took over 10 days to convert a Terabyte of data to an image. In contrast, our approach takes only about one hour”, shares NRAO software engineer Felipe Madsen.

Processing at the rate of more than 1 Terabyte of data per hour, we made one of the deepest radio images ever made with a noise of 1 micro Jy/beam.

How is this possible? Rather than sending one Mt. Petabytes to one supercomputing facility, the data was divided into pieces and distributed to smaller banks of computers with GPUs, distributed to university computing centers across the country both large and small.

The distribution of compute capacity used for these results. Data and jobs from NRAO DSOC were placed at the access point (AP) provided by the PATh project in Madison, Wisconsin. Credit: S. Dagnello NRAO/AUI/NSFThe NRAO team led by Sanjay from Domenici Science Operations Center (DSOC) in Socorro, New Mexico, working with the team at the Center for High Throughput Computing (CHTC) at Wisconsin, Madison, led by Brian Bockelman is the first to demonstrate an end-to-end radio astronomy imaging workflow harnessing computing capacity distributed across the US. “This spanned the nation from California to Clemson. We had the most universities contributing to a single, GPU-based workload, from large institutions like the University of California San Diego to small ones like the Emporia University.”, explains Brian Bockelman of the CHTC. “We believe that researchers should have quick and easy access to the nation’s investments in computing capacity and the best way to do this is through sharing”.

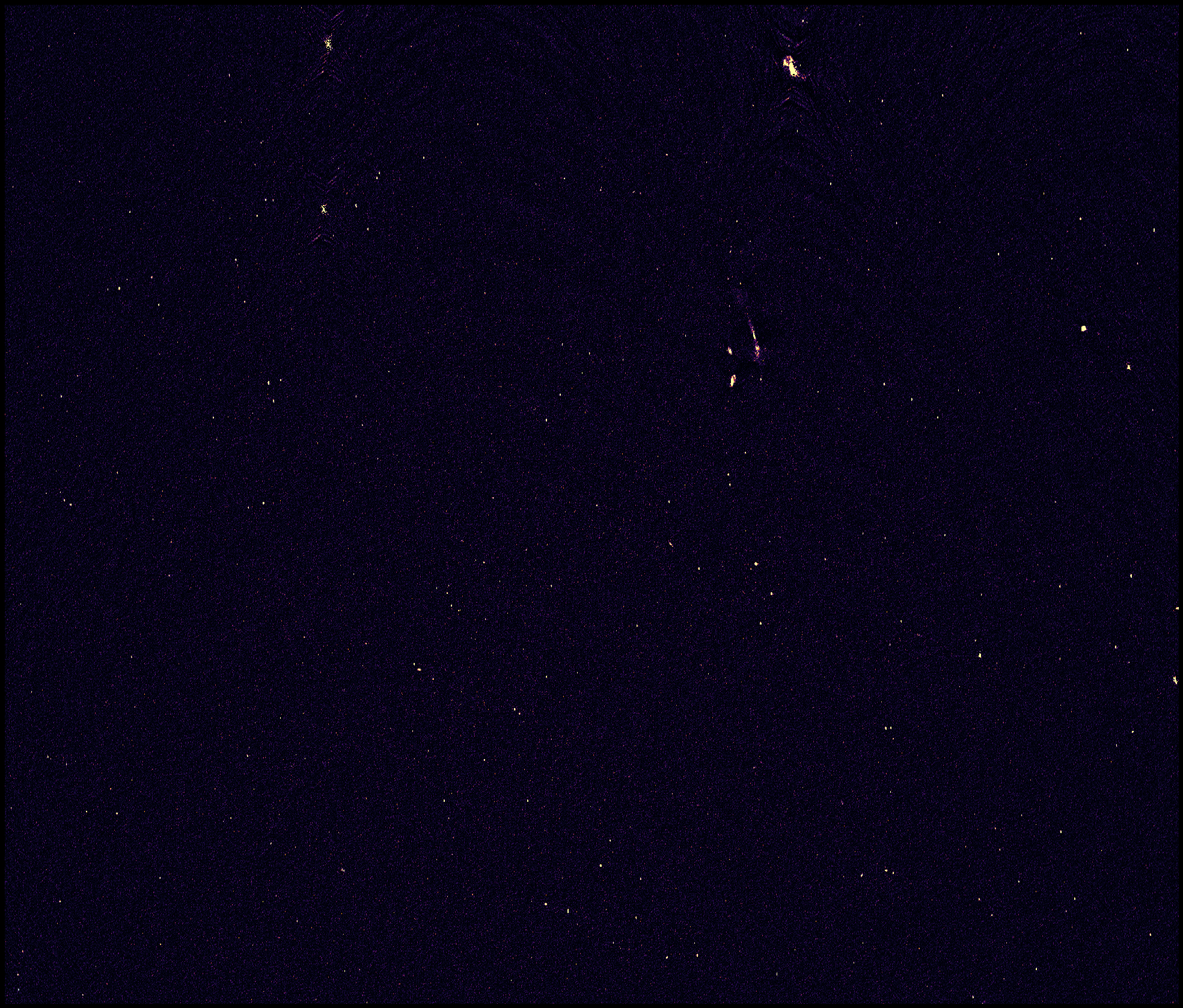

Image of Hubble Ultra-deep Field at S-BandThese distributed capacity contribution were united using open source technologies like HTCondor for computing and Pelican for data delivery, developed by the NSF-funded Partnership to Advance Throughput Computing (PATh; NSF grant #2030508) and the Pelican Project (NSF grant #2331480), respectively. These technologies power the Open Science Pool (OSPool) which stitches together the different computers amongst universities, including those in the San Diego Supercomputer Center (SDSC) led National Research Platform (NRP).

“The data was accessed via the National Research Platform (NRP) data caches deployed in the network backbone of Internet2 and federated into the Open Science Data Federation,” said SDSC Director Frank Würthwein. “NRAO thus validated a Modus operandi we expect to become more and more common as we democratize access and ownership of cyberinfrastructure for open science, especially in light of the growth of AI research and education at all scales.”

This test wasn’t just done to benefit astronomers who want to make deep images to study the universe at radio frequencies with current telescopes. It lays the groundwork for much larger projects in the future. “The next generation Very Large Array (ngVLA) will be producing 100x more data than what we used for this test. This work gives us the confidence that we can tackle large volumes of data that we’ll have from the ngVLA one day”, says Bhatnagar with cautious optimism. “We hope the success of this test inspires other radio astronomers to dream big. If the open computing capacity offered by the OSPool works for our NRAO lab, it will work for others. Researchers from small universities with little or no computing power can do this, too”.

This won’t be the last time NRAO experiments with dispersed data processing. Says Preshanth Jagannathan, a scientist in the NRAO team, “The experiment showed us where we, and the CHTC, can jointly make improvements in the way the OSPool delivers open capacity to the radio astronomers. Both teams are eagerly looking forward to the next step and continued collaboration.”

About NRAO

The National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) is a facility of the National Science Foundation, operated under cooperative agreement by Associated Universities, Inc.