| title | canonical_url | image | description | excerpt | categories | card_src | card_alt | publish_on | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Astronomy archives are creating new science every day |

|

The TRAPPIST-1 system contains a total of seven planets, all around the size of Earth.

Three of them — TRAPPIST-1e, f and g — dwell in their star’s so-called “habitable zone.”

The habitable zone, or Goldilocks zone, is a band around every star (shown here in green)

where astronomers have calculated that temperatures are just right — not too hot, not too

cold — for liquid water to pool on the surface of an Earth-like world.

|

The TRAPPIST-1 system contains a total of seven planets, all around the size of Earth.

Three of them — TRAPPIST-1e, f and g — dwell in their star’s so-called “habitable zone.”

The habitable zone, or Goldilocks zone, is a band around every star (shown here in green)

where astronomers have calculated that temperatures are just right — not too hot, not too

cold — for liquid water to pool on the surface of an Earth-like world.

|

Astronomy |

Trappist Solar System |

|

Accumulated data sets from past and current astronomy research are not dead. Researchers are still doing new science with old data and still making new discoveries.

Steve Groom serves as task manager for the NASA/IPAC Infrared Science Archive (IRSA), part of the Infrared Processing and Analysis Center (IPAC) located on the campus of the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena, California. He and his colleagues archive the data sets from NASA’s infrared astronomy missions. By preserving the data, they enable more research. One of the most valuable of these is the Spitzer Space Telescope, which was recently instrumental in confirming the existence of Trappist One, a star with several earth-like planets.

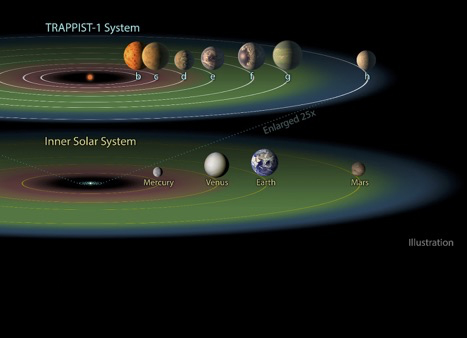

The TRAPPIST-1 system contains a total of seven planets, all around the size of Earth. Three of them — TRAPPIST-1e, f and g — dwell in their star’s so-called “habitable zone.” The habitable zone, or Goldilocks zone, is a band around every star (shown here in green) where astronomers have calculated that temperatures are just right — not too hot, not too cold — for liquid water to pool on the surface of an Earth-like world. Courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech.

“For example, we are learning how galaxies form by looking at patterns,” says Groom. A partner, the NASA Extra-Galactic Database (NED), compiles measurements of galaxies into a coherent database. Researchers discovered a whole new, previously unknown, class of galaxy (a superluminous spiral). “Theories said it shouldn’t exist, but the data was there, and someone mined the data. These huge data points need to be put to use, so new science can be done. That can only be achieved through computing.”

Figure 2: The Spitzer Space Telescope cryogenic telescope assembly (CTA) being prepared for vibration testing. Courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech.

“We are data recyclers,” says Groom. “We exist to support research that the original mission did not envision or could not do. We are now looking at computing because the data volumes are getting really large.”

Groom presented his work at the OSG All Hands Meeting in March 2017, including research highlights of science that has been done using the archive’s data. Because of this data tsunami, Groom is exploring the use of the Open Science Pool.

“New science is being done not by retrieving a single observation but by looking at large numbers of observations and looking for patterns,” says Groom. To see those patterns, researchers must process all the data or large amounts of it at once. But the data are becoming so large that they are becoming difficult to move.

“We have a lot of data but not a lot of computing resources to make available to outside researchers,” says Groom. “Researchers have computing but not the data. We are looking to bridge that gap.”

The Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE), which maps the sky in infrared wavelengths, was reactivated in 2013 and renamed NEOWISE to search for solar system objects like asteroids. The data sets consist of both images of the entire sky along with catalogs of measurements made on those images. “If a researcher wants to download the catalog, the logistics are difficult,” says Groom. “In terms of a spreadsheet—even though it isn’t in that format—it would be 120 billion rows. We recently produced a subset of 9.5 billion rows and the compressed ASCII text files are three terabytes.” The researchers must download it, uncompress it, and put it into a usable format.

Now comes the role of computing. “Researchers need access to capabilities,” says Groom. “We have limited staff, but our purpose is to help researchers get access to that data. So, we are looking for shared computing resources where researchers can get access to the data sets and do the computing. The OSG’s computing resources and good network connectivity make that a good option for the remote researcher who may have neither.”

Increasingly, they see researchers need to do large-scale data processing, like fast inventories or visualizations, and produce large-scale mosaics of survey data that are useful for researchers. The archive can use the OSG to produce these short-term reference products. Groom also wants to understand how their research partners could use the OSG. “We want to provide access without the need to download everything,” says Groom. “Data centers and other archives like us that NASA funds all have large data sets. When a researcher wants to combine data from different sites, they make that happen through high performance computing and high performance networking. We need to become like a third-party broker for the research.”

Astronomy is a relative newcomer to the need for high performance and high throughput computing. Now, astronomers have a lot more data, like physics did years ago.

“We help people get science out of existing data,” says Groom. NASA funds missions like the Spitzer space telescope, Hubble, and other survey missions to do certain kinds of science. We track publication metrics (of science done using astronomy datasets), and we look for references to our data sets. We’ve found in some of our major NASA missions that, a few years after these missions go into operation, the number of papers produced by archival research grows to exceed the originally funded missions.”

For example, a Principal Investigator can write a proposal to observe a particular part of the sky with the Spitzer Space Telescope. Once the data are public, anyone can browse the library of Spitzer data and reuse the data for their own (different) science goals, even if they were not involved with the original proposal,” says Groom.

Some researchers look at patterns in Spitzer Space Telescope images and apply machine learning techniques to look for classes of objects based on their shape. “Sometimes a star has something like a bubble shell around it (dust has been cleared out by these bubbles),” says Groom. “Researchers have adopted machine learning to look for these bubbles. They have to download huge data sets to do this. The data sets have the potential to be mined but need computing resources.”

Many other astronomy projects are also producing massive data sets. Groom’s organization is also involved in the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST) in Chile, which can take images every 30 seconds. “Astronomy is now seeing things as a movie and creating new branches of science,” says Groom. This increases the volume of data. LSST will by itself produce huge amounts of data.

The Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) at Palomar Observatory with a 600 megapixel camera, will go online this summer. It can watch things unfold in near-real time. The ZTF will observe 1 million events per night. Again, this means much more data.

Next steps

The archive is seeking to expand the resources it can offer to researchers, and find ways to better support the use of community computing resources such as OSG with those at the archive. “We either need to adjust funding or provide more funding,” says Groom. “We have to focus on the task at hand: We have all this data that needs computing. Astronomy is late to the big-data game and astronomers are new to large data sets. Our job is to help our community get up to speed. We are also talking to our peer archives to hold workshops about ways to write programs to grab data.”